The great literary chronicler of the American South and West was born Charles McCarthy in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1933. He adopted the family nickname Cormac for his writing to avoid confusion with a notorious ventriloquist’s dummy called Charlie McCarthy. A ventriloquist and his dummy are among the warped vaudeville troupe that trouble the visions of the disturbed but brilliant heroine of his last two novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, which were published in quick succession last year. McCarthy — who died on Tuesday at his home in Santa Fe, at the age of 89 — was the last conjurer of a now vanished America.

McCarthy’s prose style combined the declarative directness of Hemingway, often eschewing conventional punctuation, with the baroque inflections of Faulkner, comprising allusions that stretched from Beowulf and Shakespeare, through Melville and Hawthorne, up to Robert Frost and Allen Ginsberg. His themes were age-old and elemental: the brutality of nature, man’s tendency to fratricidal violence, Promethean temptations, incest. “If it doesn’t concern life and death,” he told an interviewer in 2007, “it’s not interesting.” He rarely granted interviews and was deceptively postmodern, drawing on the intellectual resources of Ancient Greek philosophy and the Bible, as well as systems theory and the writings of Michel Foucault.

When he was four years old, McCarthy’s family moved to Knoxville, where his father worked as a lawyer for the Tennessee Valley Authority. During the Depression, they were surrounded by poverty but relatively well off themselves, with their own home and six children. McCarthy was a Catholic altar boy and an unstudious student, with esoteric hobbies, among them writing. He was a lifelong collector of stories of violence, whether perpetrated by animals or men. These became the stuff of his novels.

He became studious in Alaska, where he was stationed after enlisting in the Air Force in the 1950s, between stints at the University of Tennessee. He said his phase of military service was the first time he read books avidly. Later he told an interviewer that there were only four novels he considered great: Moby-Dick, The Brothers Karamazov, Ulysses, and The Sound and the Fury.

Before he dropped out of university in 1959, McCarthy published two prize-winning stories in a campus literary journal. He married Lee Holleman in 1961, and they had a son, Cullen, the next year, while living in a shack in the Smoky Mountains. McCarthy’s dedication to writing put a strain on the marriage; his wife moved with their son to Wyoming and divorced McCarthy. Two later marriages also ended in divorce. McCarthy fathered a second son, John, with his third wife Jennifer Winkley, in 1999, when he was 66. He told Oprah Winfrey that the inspiration for his apocalyptic 2006 novel The Road came from staying with John at a hotel in El Paso and imagining the city on fire a century hence. The book won the Pulitzer Prize in 2007.

The road to Oprah was a long one. McCarthy’s first five novels, beginning with The Orchard Keeper in 1965, attracted few readers. His first masterpiece, Suttree (1979), a picaresque epic of Knoxville drunks and scoundrels, was his most autobiographical work. Its evocations of the city were lyrical and ominous: “Down pavings rent with ruin, the slow cataclysm of neglect, the wires that belly pole to pole across the constellations hung with kitestring, with bolos composed of hobbled bottles or the toys of smaller children. Encampment of the damned.”

McCarthy gradually acquired the attention of a cult audience and was awarded a Genius Grant from the MacArthur Foundation in 1981; among the admiring jurors was the Nobel laureate Saul Bellow. His years of poverty and peripatetic living were at an end.

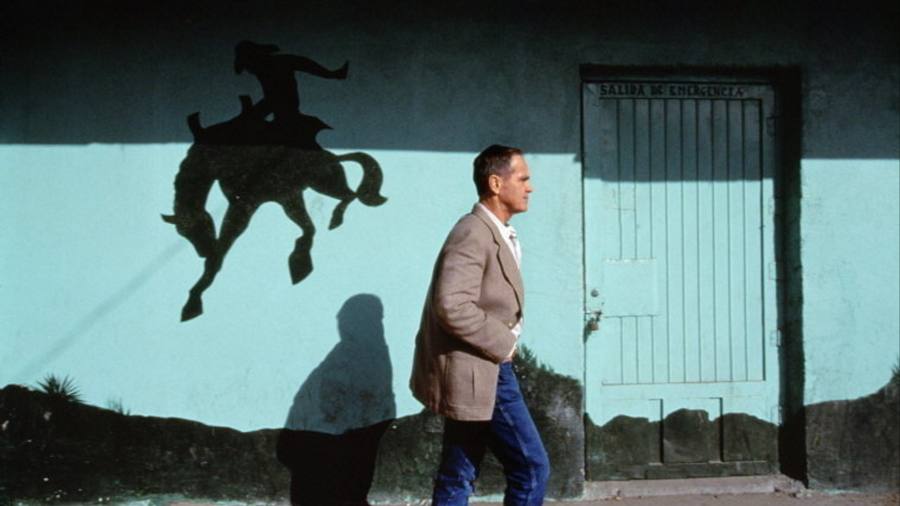

His next novel, Blood Meridian (1985), marked a turn from the South to the West, towards a territory he believed was the site of America’s mysteries. He writes of his teenage hero’s similar progress from Tennessee to Texas in the 19th century: “not again in all the world’s turning will there be terrains so wild and barbarous to try whether the stuff of creation may be shaped to man’s will or whether his own heart is not another kind of clay.” After orgies of frontier violence against Native Americans and Mexicans perpetrated by the novel’s satanic scalp-hungry villain Judge Holden, the novel ends with an oblique scene of fence posts being dug on the prairie. Man’s will has conquered the terrain, and the frontier is closing.

At the age of 58, McCarthy at last gained the literary fame his admirers had long believed he deserved. The Border Trilogy, published across the 1990s beginning with All the Pretty Horses (1992), made him a best-seller and a Hollywood commodity. The last pages of its second volume, The Crossing (1994), show the novel’s hero unknowingly witnessing the Trinity nuclear test in New Mexico in 1945, another turning point for the American West. McCarthy next published a pair of minimalist thrillers, No Country for Old Men (2005) and The Road, popular hits among both readers and cinemagoers.

From drunks, cowboys, outlaws, and wanderers in the wasteland, he moved in his last years to the contemplation of scientists and mathematicians in The Passenger and Stella Maris, which he labored composing for decades. The story of a pair of incestuous siblings, Alicia and Bobby Western, children of one of the physicists at the Manhattan Project, those final novels saw McCarthy contemplating scientific modernity as a continuation of primordial human development and self-destruction. As Alicia tells her therapist: “anyone who doesnt understand that the Manhattan Project is one of the most significant events in human history hasnt been paying attention. It’s up there with fire and language. It’s at least number three and it may be number one.”

Read the full article here