German chancellor Olaf Scholz once described his politics as “liberal, but not stupid”. As he prepares to welcome a large Chinese delegation to Berlin, a senior German official claims a similar characterisation applies: “On China you could say: we’re free traders, but we’re not stupid.”

That confidence, however, masks deep rifts within Scholz’s three-way ruling coalition, and among German businesses and Berlin’s international allies about what Europe’s most powerful nation should do about its economic dependence on China.

While all have signed up to “de-risking” — a term now also echoed in Brussels and Washington — interpretations of the concept range from restricting trade and investment in highly sensitive technologies to much more sweeping definitions.

Some in the federal government harbour doubts about the wisdom of Scholz’s light-touch approach when Germany — which in the past imported more than half of its natural gas from Russia — is striving to learn the lessons of Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

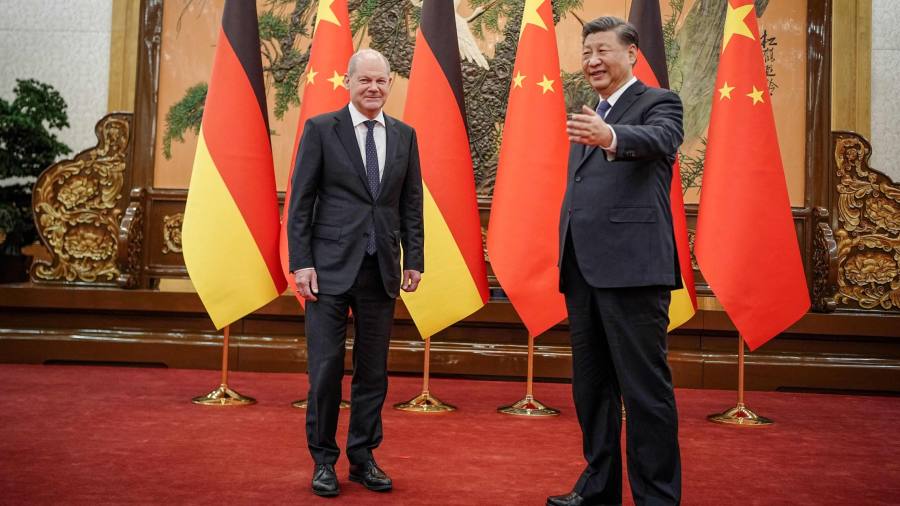

The seventh joint German-Chinese government consultations, due to begin on Monday, will be the first face-to-face meeting since the coronavirus pandemic. It will also be the first overseas visit by new premier Li Qiang. Li, a former Communist party secretary of Shanghai who convinced Tesla to build its first overseas factory in the city, will meet German business leaders and ministers.

The consultations come at a time of strain within the EU and the G7 group of the world’s richest nations about how to handle the deep tensions between the US and China and the issue of Taiwan. French president Emmanuel Macron was criticised in April after saying during a state visit to China that it would be a “trap for Europe” if it got “caught up in crises that are not ours” — a reference to the Sino-American frictions.

German officials say Scholz has gradually grown more wary of China and is not blind to the risks. Under pressure from the US, Berlin announced earlier this year that it would review the use of telecoms network components made by the Chinese manufacturers Huawei and ZTE.

But the chancellor is more dovish than Green coalition partners — led by foreign minister Annalena Baerbock and vice-chancellor Robert Habeck — who advocate a tougher approach towards Beijing.

Last month Scholz overruled Green objections to approve a plan for a Chinese conglomerate to take a 24.99 per cent stake in a Hamburg port terminal.

“The core priority for German de-risking is critical raw materials and the supply chain,” said Mikko Huotari, executive director at Merics, a Berlin-based think-tank focused on China. A more integrated approach would also appraise the role of Chinese companies in Germany’s critical infrastructure, technology controls, including outbound investment screening, and the over-dependency of German companies on China, he added.

German officials say the chancellor is aligned with US national security adviser Jake Sullivan’s vision of a “small yard, high fence” that seeks to closely guard critical technologies without casting the net too wide.

Days before the arrival of the delegation from Beijing, which will include Chinese ministers and business executives, Scholz’s cabinet adopted its first-ever national security strategy. It described Beijing as “increasingly aggressively claiming regional supremacy” and “repeatedly acting in contradiction to our interests and values”.

Still, China was Germany’s largest trade partner for the seventh consecutive year in 2022 with bilateral trade worth almost €300bn — a figure that dwarfs the country’s trade with Russia before its invasion of Ukraine. Flows of German foreign direct investment into China reached an all-time high of €11.5bn in 2022, with the total stock of German FDI in the country preliminarily estimated to have reached €114bn that same year, according to the German Economic Institute in Cologne.

And the country’s powerful carmakers — Volkswagen, BMW and Mercedes-Benz — all count China as their largest market and invest accordingly to defend their market share amid growing competition from Chinese brands.

Despite government warnings, executives at the carmakers, chemical giant BASF and industrial bellwether Siemens have all vowed to defend and expand their presence in China. One senior European official quipped that big German industry was “decoupling from the government” on China.

Yet trying to hamper German companies that are earning big profits in China would be “stupid”, the senior German official argued. “Of course we fear mainland China invading Taiwan. But because of that, should we commit suicide?”

Others in Berlin see it differently. They fret about the consequences of letting some of the country’s most powerful manufacturers remain wilfully blind to the geopolitical risks. “I don’t care if Mercedes or BMW are heavily investing. I care if they go bankrupt at some point,” said another senior government official. “Imagine a scenario where [all the big carmakers] lose access to China.”

German officials and industry representatives say that, away from the motor and chemicals industries, business attitudes towards China are shifting, with Mittelstand companies that are the backbone of the German economy taking a more cautious approach to geopolitical risks.

A recent survey by the German Chamber of Commerce in China found that, while nearly 55 per cent of German companies plan to make further investments in China, that figure remains far below the early pandemic level of 72 per cent despite the lifting of Beijing’s strict “zero Covid” restrictions.

De-risking is “a no brainer”, said Wolfgang Niedermark, a member of the executive board of Germany’s largest business lobby, the BDI. “It’s happening whether you like it or not.”

China’s top priority during next week’s talks will be to “put Germany-China relations back on the right track” after all the talk of de-risking, the Ukraine war and prolonged lack of contact during the pandemic, said Wang Yiwei, director of the Institute of International Affairs at Renmin University in Beijing. China has been on a European charm offensive and also sees economics as the “cornerstone” of its relationships in Europe.

Premier Li will also be seeking to ease Germany’s concerns over supply chain security, Wang added, and to persuade German companies to resist recent trends by retaining China as a global base rather than using it to produce solely for the domestic market.

The German side hopes to focus on climate policy, with the aim of persuading the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide to agree to more ambitious targets on reducing emissions and accelerate investment in renewables. But Li Shuo, senior policy adviser for Greenpeace east Asia, cautioned that success on that front was unlikely. “China does not want to be seen to cave into international pressure,” he said.

German ministers will also raise the issues of Taiwan as well as China’s support for Vladimir Putin in the war against Ukraine, even as they concede that progress is unlikely.

Huotari, the Berlin-based China expert, said Germany’s welcome would be seen as a triumph in Beijing. “The way they see it, they won Macron and now they are winning the Germans. I don’t think that is true but that’s the way they see it.” He added: “For the Chinese, the meeting will be the message.”

Additional reporting by Guy Chazan in Berlin

Read the full article here