Try to get your head around the magnitude of American power in 1955. The US had set up Bretton Woods and Nato. It had revived Japan and western Europe. It led mass culture (Hollywood, Elvis Presley) and high art (Abstract Expressionism, Saul Bellow). It had a monstrous share of global output. It had leaders as far-sighted as Dwight Eisenhower.

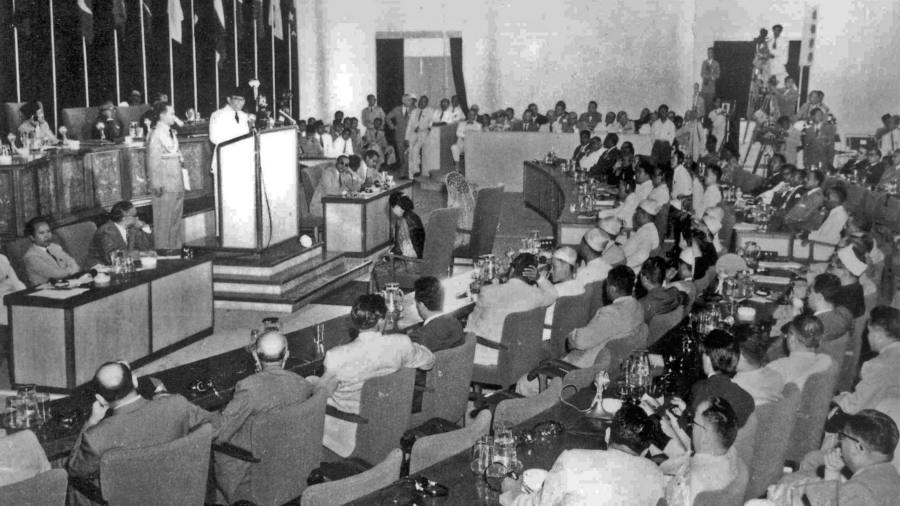

And it couldn’t stop half the world’s people going their own way. As the cold war solidified around them, the non-aligned countries met that year in Bandung, Indonesia. If the west, at its mightiest and best-led, couldn’t charm, induce, reason or bully them into its camp, who could blame it for failing to do so now?

Quite a few, it seems. The west is losing the “rest”, I keep reading, especially on the question of Ukraine. Two problems stand out here. First, to lose something, one must have once had it. When was that? Second, these countries have agency of their own. That includes the power to be wrong.

At root here is the undying belief that, if something in the world is awry, the US and its allies must be culpable. This allows western progressives to feel their favourite emotion: ostentatious guilt. It opens the door for their favourite and perhaps only idea: financial transfers, whether in the form of aid or infrastructure investment or debt relief. Their self-criticism has a veneer of humility. But nothing could be more patrician. The thing about guilt is that it assumes one has ultimate control over things.

Although the west has secularised, one biblical notion lives on: that there is virtue in suffering. To be wronged is to be right. This idea needs countering at every point. That a nation is poor does not make its worldview true. That it was brutalised in the past does not validate its judgment on a separate subject a human lifetime later. (Any more than Christ’s ordeal validates the gospel.)

It is possible that the “global south” — not all of us who were born there take the neologism seriously — is just wrong about Ukraine. Wrong morally, because the war is a case of imperial conquest, which former colonies profess to oppose. Wrong strategically, because there isn’t much to gain from courting Russia as an alternative patron to the US. (If Washington is high-handed, try Moscow.) Above all, wrong independently. The fence-sitters over Ukraine weren’t put there by the US. The US can’t charm them down either.

You needn’t agree, by the way, that the global south is wrong. The point is, what is the west meant to do? These are independent states. Among them is the largest nation on Earth (India), resource superpowers (the Gulf states) and perhaps the strongest military in the southern hemisphere (Brazil). Poor in the Bandung era, many are now middle-income. The west, meanwhile, is a dwindling share of world output.

In much of the globe, the west stands accused of sanctimony. Let us break that vague complaint down into specifics. Russia can offer countries a place in its economic and military orbit without moral strings attached. It does not ask them to make internal liberal reforms, for example. Are these terms something that critics of the west think it should match? If so, that isn’t a disgraceful idea. (The cold war wasn’t won by ethical fusspots.) But it would be nice if someone spelt it out. At the moment, there is lots of hiding behind evasive waffle about the need for “engagement”.

The west has engaged — as a donor of aid, as a receiver of immigrants, as an underwriter of security — since 1945. If that has failed to elicit support for its view on Ukraine, then lots of things are at work. One is sincere resentment of the west’s colonial past. Another is cold (and again legitimate) calculation: a strong Russia and China allows poor countries to drive a harder bargain with the US. Yet a third is muddle-headedness about events far away. “If one doesn’t want to, two can’t fight,” said Brazil’s president, of Ukraine, in what he must have believed was an insight. The rest, I’m afraid, is bad faith, often from global South elites whose mistrust of the west exempts London real estate, Paris luxe retail and US universities.

Against this wall of intransigence, the west must keep knocking. But it must also accept that other countries can, of their own volition, and for no want of persuasion, err. Non-alignment in the cold war wasn’t such a wise bet in the end. It led many governments to adopt quasi-socialist policies that have taken decades to undo. As for south-south solidarity, several Bandung-attending countries would later go to war with each other. How delinquent of the west to let that happen.

Read the full article here