I was once, as an intern, told by a veteran reporter that if I was ever asked the classic “What do you think makes a good journalist?” question in a job interview, there was only one correct answer: paranoia.

I confess to having been somewhat perplexed at the time, but 10 years later, I get it. I wasn’t being encouraged to go around imagining that everyone was out to get me. Rather, I was being reminded of a journalist’s responsibility to publish accurate and fair information. It was a warning against complacency. A nudge, if you like, to hold on to a little bit of good old-fashioned anxiety.

He needn’t have worried too much about me: I’m fairly familiar with anxiety’s pulse-quickening, breath-shortening charms, which extend to my work. But he was also tapping into an idea that a growing body of research is pointing to: anxiety is not something we can or even should always try to eradicate entirely, and that we actually need a bit of it to perform well, and even to help us lead happy and fulfilling lives.

Of course, it should be said that beyond a certain point anxiety can become debilitating, and clinical intervention is needed to deal with serious anxiety disorders. But we seem to live in a society that is increasingly anxious about anxiety’s very existence.

It was the theme of last week’s mental health awareness week, run by the Mental Health Foundation. On the foundation’s “anxiety statistics” page we are told that in 2022-2023, 37 per cent of women and 30 per cent of men in Great Britain reported high levels of anxiety, up from 22 per cent and 18 per cent respectively from 2012 to 2015 — a rise that is often attributed to increased social media use, as well as worries about external threats from climate change, AI and pandemics. Above the statistics, there is a warning: “This content mentions anxiety, which some people may find triggering.”

But what if part of the problem is that we are thinking about anxiety the wrong way? A study published in Emotion, a peer-reviewed journal, in March found that judging emotions as positive or negative may have crucial implications for our wellbeing.

“Meta-anxiety — anxiety about anxiety — is exactly the thing that’s destroying us,” Tracy Dennis-Tiwary, a clinical psychologist and author of Future Tense: Why Anxiety is Good For You (Even Though it Feels Bad), tells me. “That’s why we’re having this mental health crisis now. We’re talking about it incorrectly.”

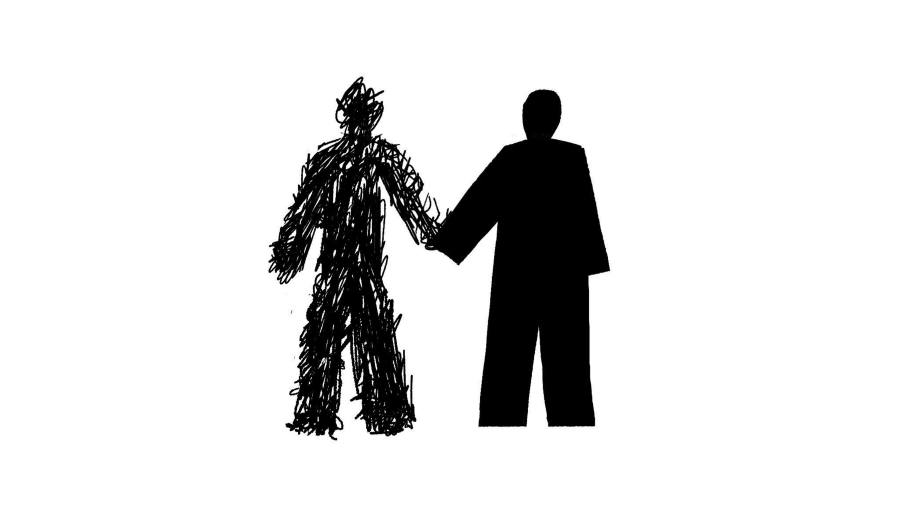

Dennis-Tiwary says that rather than trying to avoid anxiety, we should be facing it to build skills and emotional resilience that help us manage it. Further, by framing it negatively, we miss out on the opportunity to harness the more positive features it can bring: vigilance, focus, motivation and a burst of energy that can help us perform at our best.

If we don’t always frame it as a negative, we can experience what some neuroscientists call “good anxiety”. “Good anxiety is situational, time-limited and very motivating,” Morra Aarons-Mele, author of The Anxious Achiever: Turn Your Biggest Fears Into Your Leadership Superpower, tells me. “It’s the anxiety that we need to do great things, and often the anxiety that we feel because we care, because we’re emotionally invested in the outcome, because we want to be excellent. Because we’re scared as hell, we go for it.”

All of that is very well, you might think, but given how cripplingly awful anxiety can feel, how can we tap into the “good” variety when we are in the grips of its horror? One way is to respond physiologically: doing breathing exercises that let us know we are safe by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system, or undertaking physical activity, which releases feel-good endorphins and serotonin.

But another technique is something that Harvard Business School psychologist Alison Wood Brooks has called “anxiety reappraisal”. When we are feeling anxious, our bodies and brains are in a state of increased arousal and alertness that is similar to — and sometimes indistinguishable from — excitement. Our heart rate quickens, adrenaline surges and we prepare ourselves for action. Brooks’ research suggests that reframing anxiety with simple tweaks — such as saying “I’m feeling excited” rather than “I’m feeling anxious” — can be surprisingly effective.

Of course, when anxiety has reached a point at which it is difficult to go about daily life, such techniques are unlikely to be sufficient. But if we experience it at a more moderate level, we should try to see it for what it is: a normal, even healthy human emotion that our very survival as a species has relied upon. If you’re never anxious, you’re probably not alive.

Read the full article here