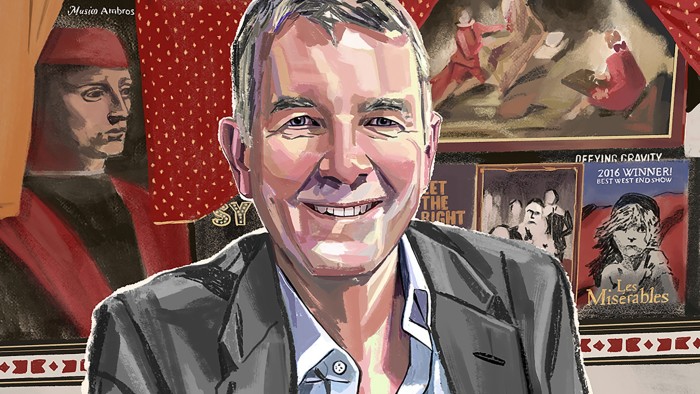

The setting is worthy of a spy novel: the narrow, softly lit Mediterranean joint down a cobblestone Soho street, the bright-coloured curtains draping rough plaster walls, the somewhat gauche posters of West End plays and Renaissance art. I imagine hushed conversations, an agent meeting a source, or luring a recruit, over a kebab and a glass of wine. My guest, Sir Richard Moore, until recently Britain’s spy chief, will not share whether the unimaginatively named Mediterranean Cafe has featured in his clandestine career: “I couldn’t possibly say.” But he is a regular at the haunt, knows Ali, the owner, and is familiar with the Turkish menu.

We are meeting a month after the 62-year-old Moore stepped down as head of the Secret Intelligence Service, popularly known as MI6, closing a 38-year career that started at the tail-end of the cold war and included a four-year stint as the British ambassador to Turkey, a country for which he holds particular attachment. He first served there as an intelligence officer early in his career, after learning the language by accident; he had made the mistake of declining to take up first Chinese and then Arabic. “Someone in HR turned up and looked me in the eye and said, ‘When you’re asked a third time, you will say yes, I would like to learn Turkish.’”

A few weeks before our lunch, he marked the end of his MI6 career with a speech in Istanbul, in which he referred to Turkey as his second home. “If you learn a foreign language properly, part of you gets invested in that country and culture,” he tells me. “I swear that I’m a slightly different character in terms of who I am . . . more Mediterranean, more expressive.”

Whether it is the Turkish or the diplomatic influence, Moore was an unusual “C”, as Britain’s spy chief is known, more public-facing than his predecessors, and more willing to take on internal critics who considered him too progressive. He came in with a mantra — that MI6 needed to be “more open to stay secret” — and pledged that he would be the last C to be picked from an all-male shortlist. That he maintained a Twitter (now X) account and sometimes even tweeted in Turkish rankled with his more traditional colleagues. I’ve heard that some senior men were upset by what they perceived to be a deliberate plan to bring on a female successor.

Moore, who resigned from the exclusive Garrick Club in 2024 after being criticised for remaining a member of the then men-only organisation, dismisses “small vocal constituencies”. He is visibly delighted that Blaise Metreweli prevailed (from a mixed-gender shortlist) as his successor. The first woman to hold the post previously led the agency’s technology and innovation division (she is “Q” in James Bond parlance), expertise that Moore considers critical for the future of spying.

Moore describes his greater openness to the public and the media as an evolution, rather than a departure from his predecessors. It was necessary to try to fix some of the problems the agency was facing, whether in recruiting women and ethnic minorities or encouraging tech companies to propose creative ideas. An intelligence service, he argues, has a particular need for agents from minority backgrounds, who can blend more easily into — and bring a deeper understanding of — certain environments. But Moore has also used his public appearances to encourage defections, particularly from Russia after the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Today, MI6 has a “wonderful” portal on the dark web to attract new spies, which Moore announced in his Istanbul speech. Not having yet fully stowed his recruiter hat, he says: “There is urgency about [Russia] but if some Iranians or some other nationalities would care to apply, that’s fine too.”

For some mysterious reason, Mediterranean Cafe has gone slightly Georgian, but Moore suggests we stick to the Turkish menu. He picks the starters — a meze plate that includes hummus and dolma (stuffed vine leaves) and another plate of grilled halloumi cheese served with sujuk, a spicy fermented sausage. For his main course, he orders the lamb kofta (meat with herbs, onions and spices), while I plump for the plainer chicken kebab. I choose a Georgian dry white wine and discover the Marani Rkatsiteli to be crisp and refreshing. Moore orders a glass of 2018 Mukuzani red, also declaring it satisfying.

Moore is soft-spoken, like the diplomat he once was, and utterly deliberate, like a spy. He is casual, his white shirt unbuttoned at the neck, under a dark suit. He declares that he intends to remain relaxed. His name has been raised as ambassador to the US, a job he is not interested in, and he says he’s enjoying talking to people about what he might do next. His tenure as head spy was extraordinarily tumultuous, spanning a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, the return of war in Europe, the emergence of China as a more assertive global power, the comeback of Donald Trump and a wider Middle East war. “I have not left the world in a better place,” he says in a model of British understatement. “We are now clearly in a highly contested world . . . a world of loose ends.”

He’s also left a world in which European liberal values are challenged and the UK and the continent are squeezed between two overbearing powers — the US and China. I tell him I’ve just returned from China, where I repeatedly heard that Europe was now living off a glorious past, that it had grown weak, perhaps even lazy. “Fundamentally, some of the issues here are around our own self-confidence, aren’t they?” says Moore. “We have, since I guess the global financial crisis, a narrative of western weakness that has really taken hold in Chinese minds . . . And so it’s up to us to change that narrative. It’s been difficult because frankly our politics has been pretty disruptive, hasn’t it?”

He notes that during his time as chief, he served two monarchs (“I can’t really blame the Queen”), four prime ministers, five deputy prime ministers and six foreign secretaries. “In that environment, it’s been difficult, I think, for a country like the UK to get the consistent narrative of our strengths in the international system.” What he calls the power of example was a potent weapon in winning the cold war. “Getting ourselves to a point where we recover our power of example is the strategic play.”

It’s not easy to change the narrative when the UK’s major ally, the US, launches a tariff war that punishes friends as well as foes, and foreign policy priorities shift according to the whims of the president. Can the intelligence relationship with the US — the tightest of all — survive the Trump administration, if perceptions of threats do not always converge? Moore hesitates for a second, telling me of the extent of his personal investment in the US. He won a postgraduate scholarship to study at the Kennedy School at Harvard University after his Oxford degree, and returned to America years later to attend a Stanford executive programme. Remember the 1956 Suez crisis, he says, when the US and UK were at loggerheads; he concludes that “differences within the family” will be overcome, as they have been in the past.

Moore worked closely with his then CIA counterpart, Bill Burns, on successfully identifying and publicising Russia’s intentions on the eve of the Ukraine war. For a generation of spies scarred by the calamitous intelligence failures of the Iraq war, that public warning was a major triumph, even if Russian tanks soon rolled into eastern Ukraine. Moore says that under the Trump administration the intelligence relationship remains intact (although it emerged this week that the UK had paused some intelligence sharing on suspected drug vessels in the Caribbean): in this sphere the CIA is the most important foreign relationship for the UK, and MI6 the most significant for the US. But how does Moore feel about Trump’s on/off attempts to strike a deal with Vladimir Putin over Ukraine, on terms that are uncomfortable for Kyiv and indeed for the UK? He brushes aside the European exclusion narrative. “I fundamentally assess that Putin is not interested in negotiations. There are no negotiations, not real negotiations. He’s attempting to play us.”

According to Moore, there are two Putins. One is the cold-eyed realist, the ruthless leader who cuts deals when he has to. This is the Putin who last year accepted the loss of Syria and the ousting of his ally, the dictator Bashar al-Assad, and sought only to protect Russian bases there. The other Putin is ideological and has “a deeply wired feeling that Ukraine doesn’t have the right to exist”. This Putin invaded Ukraine and his objective, says Moore, is not to bargain over slices of territory but to dominate.

In Moore’s view, the only way to confront the ideological Putin is to pile so much pressure on him that he is forced to choose between fulfilling his legacy project in Ukraine and holding on to power. That’s why Moore argues that Ukraine should have the right to strike deep into Russia, and that more economic pressure should be brought to bear on the Putin regime. “This is a very, very winnable contest,” he says. “It’s particularly important that we don’t snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.”

Moore likes the Mediterranean Cafe because it’s not cavernous and you can hold a comfortable conversation. The food is also unpretentious yet wholesome. The garnish may be clumsily sprinkled on the starters but the sujuk is juicy and perfectly spiced, and the kebab simple but tasty. I am eating faster than my guest, who remembers that he is going out to dinner, as we move from one intelligence threat to another.

When Moore started as spy chief, he identified “adapting to a world affected by the rise of China” as the single greatest priority for MI6. Much of the concern related to China’s technological and surveillance advances and their export to other governments. British intelligence had to understand Chinese decision-making but also learn to operate undetected within the surveillance web, a challenge made all the more tricky today by artificial intelligence. China is “incredibly well resourced . . . they have scale and persistence, and a long-term approach, and therefore we as a society need to get ourselves prepared to be resilient enough to withstand that probing”.

We move on to the recent controversies testing the UK-China relationship. What does Moore make of the row over the Chinese “mega embassy” in London? Plans for the largest embassy in Europe, on a five-acre site near Tower Bridge, have been delayed, with China hawks saying it poses a threat to national security. Attempts to refurbish the British embassy in Beijing, meanwhile, are stuck. Moore is sanguine, and says there has to be a compromise. “They obviously need an embassy. We need one too.”

Another scandal recently erupted over the collapse of a Chinese spying case after the government refused to tell prosecutors that Beijing posed a clear national security threat. I ask him whether the unravelling sends the wrong message to Beijing. “I’m not very keen on people being over-moralistic about the fact of spying,” he says, pointing out that he led an organisation which did precisely that. Insisting he won’t comment on the case itself, he nonetheless reflects on the consequences. “More broadly, I am a firm believer in deterrence. If you are tough-minded and clear about the things which are unacceptable. And clearly spying on us — if we catch them — is certainly unacceptable.”

Moore and I are disappointed that Turkish coffee, the thick unfiltered brew that concludes meals in many parts of the Middle East, is not on the menu, and we order espressos. We’re discussing how the business of spying has changed in the age of disinformation and biometrics. An agent today is more easily detected, and perhaps less likely to be charged with recruiting a human being than with breaking into a data system. So is human intelligence less or more important than ever?

Definitely more so, he says. “There is technology arrayed against us which makes aspects of what we do difficult, and we have to overcome those challenges. On the other hand, we’re operating in an increasing wash of disinformation . . . There is a huge appetite for verified fact because it’s increasingly rare and ours [human resources] . . . is one of the higher ends of it.”

I ask Moore about fictionalised accounts that come close to the reality of his old job. He points to The Bureau, the French TV series that includes in its credits the French intelligence service, and is one of my favourite shows. “Everything is accelerated, everything is slightly more extreme . . . it feels pretty good and the characters are well developed and you might recognise one or two of those people around the corridors.”

When we move to who should play the next James Bond (the only name that comes to Moore’s mind is Eddie Redmayne), we are joined by Ali, the owner, who started at the restaurant as a kitchen porter 26 years ago. Ali is in fact a Kurd from Kahramanmaraş in eastern Turkey and Moore demonstrates once more his deep knowledge of Turkey’s geography and history as he muses about the region. His special relationship with Turkey has undoubtedly been a glue in UK-Turkish relations, and he is said to have earned the enduring trust of strongman Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, after reassuring him after the failed 2016 coup that Britain stood with him. In that farewell speech in Istanbul, Moore referred to Turkey as “a nation of pivotal importance to the international system”.

And yet, there’s plenty to criticise about Turkey. Once lauded as a model Islamist-rooted democrat, Erdoğan has turned Turkey into an authoritarian repressive regime. Isn’t Moore too soft on him? “Of interest to me is the role they play, and I am positive about the overall balance of what Turkey brings to the party and the international system.”

As we leave the restaurant and go our separate ways, through the vegetable market stalls of Berwick Street, I wonder why we are so drawn in by the mystique of spycraft. We are seduced by the spies’ stories, the books and the films. We know their business is intractable at times, always hidden and often shifty. Those they trust could be from the most dubious of regimes. Perhaps we find their opaque trade an escape from realities we prefer not to see. As Moore remarked during our lunch, to be a good spy “you have to be prepared to take the world as it is, not as you would like it”.

Roula Khalaf is the editor of the Financial Times

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here