Novo Nordisk is about to discover the outcome of a gamble that investors hope can transform the drugmaker’s ailing outlook: can its weight loss drugs be used to treat Alzheimer’s?

Ahead of the results from two studies of thousands of people in the early stages of the disease, Ludovic Helfgott, executive vice-president for product and portfolio strategy, recently acknowledged that Novo has always seen the trials as a “lottery ticket”. It is a high-risk, high-reward bet that has the potential to revive the Danish company’s beaten-down share price.

The phase 3 trials — which are set to publish results this quarter — are trained on an area of huge need: to help treat some of the 55mn people around the world with dementia.

On the face of it, the chances of success appear slim: the vast majority of experimental drugs for Alzheimer’s have ended in failure. Those that have successfully come to market in the past few years, from the likes of Eisai and Biogen, and Eli Lilly, can only slow cognitive decline. Nothing so far has been able to reverse it.

Despite that, some shareholders are starting to view the trials — which use a synthetic version of the GLP-1 hormone that regulates blood sugar — more positively.

One manager of a healthcare fund that owns Novo shares said the prospect was “super interesting scientifically” describing the GLP-1s that are the active ingredient of Wegovy and Ozempic as “wonder drugs”.

So far, they have certainly proved highly successful for treating diabetes and obesity, while studies are already showing much more wide-ranging effects, including reducing the risk of heart attacks and strokes and improving kidney function.

Novo Nordisk shares have fallen more than 55 per cent in the past year, thanks to a combination of disappointing trial results for a new obesity treatment, its failure to stay ahead of Eli Lilly in the US market and competition from cheaper, replica obesity drugs.

The sharp decline in the drugmaker’s shares meant greater potential for a reaction to any positive news from the trials, added the fund manager. “The risk/reward has definitely changed,” she said.

Scientists have been exploring the potential effects of GLP-1s on the brain since the early 2000s. Christian Hölscher, a professor of neuroscience at Henan University in China who works on developing treatments for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, started working on the link around 2007.

He said that Novo initially had little interest in the possibilities of GLP-1s in neuroscience, a field where it has no existing products. But in 2020, a trial Hölscher was working on, studying semaglutide predecessor liraglutide, “totally changed their mind” in his view. The early stage study found that liraglutide slowed disease progression in Alzheimer’s patients. “Almost the next day, Novo Nordisk announced these two massive trials,” he said.

The company is running two trials, each with 1,800 patients and lasting three years and four months, across 30 countries. They were due to end in September and then move on to data analysis. Hölscher said that in the field of dementia, the scale of the research was “colossal . . . I’ve never seen clinical trials like that before, so this is going to give us the definite answer”.

Novo Nordisk said the decision to do the trials was based on many studies with semaglutide and other GLP-1 drugs, in humans and animals.

Chief scientific officer Martin Lange said the evidence that encouraged Novo to pursue large trials included a study of the medical records of people with diabetes who had been taking semaglutide for two years. This found a 53 per cent reduction in dementia diagnoses — a “highly statistically significant” result. Other studies of people taking semaglutide over the same period found a 21-43 per cent reduction in the risk of a dementia diagnosis.

Even among those who believe semaglutide has potential as a treatment for Alzheimer’s, there is debate over how it would work. One common theory is that GLP-1s could mitigate an excess of sugar in the brain that some think leads to inflammation, accelerating the build-up of amyloid and tau proteins that are characteristic of the disease. This excess sugar could be one reason why people with obesity or diabetes are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s.

“If you have obesity, there’s an approximate doubling of the risk of getting Alzheimer’s and, if you have diabetes, there’s approximately a tripling in risk that, in part, is suspected to be due to poor metabolic control in the brain,” Lange said.

Hölscher believes inflammation is central to the disease and that the amyloid plaques, which existing drugs target for clearance, are “most likely just some side-effect” rather than part of the root cause.

But Ivan Koychev, associate professor of neuropsychiatry at Imperial College London, holds that amyloid and tau are an important factor in causing Alzheimer’s. He also believes the most plausible explanation for the sharp drop in dementia diagnoses among semaglutide users in just a couple of years is the effect of the drug on inflammation — one of the main drivers of the disease.

“There’s a very strong effect of these medications on systemic inflammation,” he said. “There also seems to be a specific effect on neuro-inflammation.”

Koychev is running a study to find out more about effects of GLP-1s on the brain. He said other hypotheses need to be considered: perhaps they reduce the incidence of strokes, a risk factor in developing dementia, or modify insulin levels, which are thought to contribute to the accumulation of tau in the brain.

Other experts remain doubtful of the chances of success. Sir John Hardy, chair of the molecular biology of neurological disease at UCL, said he does not believe GLP-1s will prove to have a direct, disease-modifying effect on Alzheimer’s.

“Frankly, I’m not expecting a positive outcome. That’s my prediction, but having made that very clear prediction, I should say that I’ve been wrong plenty of times,” he said.

Hardy thinks it is more likely that if GLP-1s do have an impact on dementia, it will be because of secondary effects such as a reduction in damage to blood vessels. According to the Alzheimer’s Society, at least 70 per cent of people with the disease may have damaged blood vessels in the brain.

He explained that other public health improvements — such as better control of blood pressure and cholesterol and lower rates of smoking — have contributed to the incidence of dementia dropping over the past 30 years in wealthier countries. “Maybe giving people GLP-1 agonists would be another factor in improving your blood chemistry, so that you get less vascular damage and less dementia,” he said.

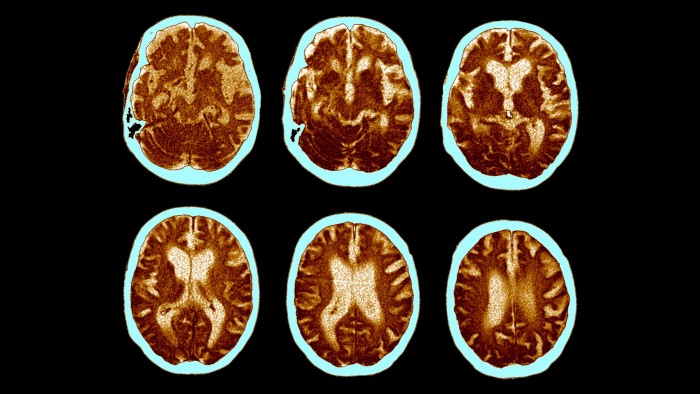

However, the Novo trials focus on a different stage of the disease: all of the participants already show a build-up of amyloid on brain scans.

If GLP-1s work only on those who do not already have this build-up, instead preventing Alzheimer’s before it has started, the trial will look like a failure.

Scientists and investors will all pore over the details when the results are published to assess for whom the drug will work — and therefore how big the market could be.

Lange said that, with such a “huge unmet need”, any result that is statistically significant will be “clinically meaningful”.

Evan Seigerman, an analyst at BMO Capital Markets, believes even a small improvement over placebo could push Novo Nordisk shares up 5 to 10 per cent. “Sometimes the long odds aren’t as long as you think,” he said.

Read the full article here