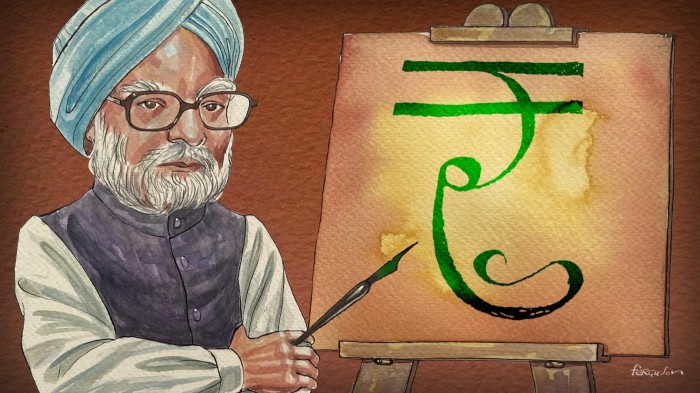

The achievements of Manmohan Singh, who died at the age of 92 on December 26 2024, make him one of the most important policymakers of our era. Today’s economically dynamic India is his legacy. Almost as significant is the example he gave of intelligent, informed and honourable public service. Singh took ideas seriously, yet was unfailingly courteous and open to the ideas of others. I had the privilege of knowing him from 1974, when I was a senior economist in the World Bank’s India Division and he was the government of India’s chief economic adviser. He was one of the greatest men I have known.

Singh’s most important achievements as a policymaker were made during his years as finance minister from 1991 to 1996. He was appointed, to his surprise, by prime minister PV Narasimha Rao, at a time of a huge foreign exchange crisis. Cometh the hour; cometh the man. He seized the opportunity to deliver radical reform of an anti-trade and anti-market policy regime that had crippled India’s economy since independence. He had known of these errors since he wrote India’s Export Trends, his doctoral thesis at Oxford, published in 1964.

With the prime minister’s backing, Singh duly transformed India’s policy regime. The reforms ultimately included radical trade liberalisation, deregulation of industry, liberalisation of finance and a shift to a more modern monetary regime, without direct monetary financing of the government by the Reserve Bank of India.

The subsequent transformation in Indian economic performance is dramatic. Over the 41 years from 1950 to 1991, real GDP per head (measured at purchasing power parity) increased by 108 per cent. Over the shorter period of 32 years from 1991 to 2023, it rose by 360 per cent. This was a jump from trend annual growth of 1.6 per cent to one of 5.2 per cent. Roughly speaking, the post-1991 trend and the broad policy regime have persisted ever since.

The past three decades, then, have transformed India. Whether this will be sustained in the decades ahead is unknown. Whether India will become the developed country it aspires to be in 2047, a century after independence, is also unknown and, in my view, rather unlikely. But India’s population is the largest in the world, at 1.4bn and rising. If growth continues, it will be an economic superpower by then.

Yet China’s real GDP per head rose by 1,150 per cent between 1991 and 2023, — an astounding trend annual rate of 8.4 per cent. Moreover, surprisingly, the share of manufacturing in Indian GDP has fallen, according to the World Bank, not risen, as one would have expected, from 16 per cent in 1991 to 13 per cent in 2023. Again, while ratios of trade to GDP soared after the reforms, they have fallen back somewhat more recently.

Inequality also seems to have risen. According to the World Inequality Database, the share in income of the top 1 per cent soared from 10 per cent in 1991 to 23 per cent in 2023, while the share of the top 10 per cent jumped from 35 per cent to 59 per cent. Meanwhile the share of the bottom 50 per cent fell from 20 per cent to 13 per cent. This data is contested. Yet even if true, this would still imply an increase of 180 per cent in the real incomes per head of the bottom 50 per cent over the period. Moreover, by 2023, the average real incomes of the bottom 50 per cent were slightly above the all-India national average in 1991. The absolute number of people in extreme poverty and so the proportion, too, have collapsed. Fast growth is, as always, the most powerful way to eliminate poverty and improve opportunity.

Singh’s period as prime minister from 2004 to 2014 is more controversial than his period as finance minister. He was appointed by the leader of the Congress party, Sonia Gandhi. Indian democratic politics are deeply tainted by money. Yet he remained untainted. Moreover, as Pratap Bhanu Mehta argues, his achievements are underrated, partly because of the defeat by Narendra Modi’s BJP in 2014. Yet they were substantial. They include the nuclear deal with the US, which ended the long-standing friction between the two countries. They also include the national rural employment guarantee scheme of 2005. Not least, in 2009 his government invited Nandan Nilekani of Infosys to launch India’s unique identification system (Aadhaar), on which many of the BJP’s reforms have been based.

Singh was a global asset for India. Montek Singh Ahluwalia, a friend of mine since I joined the World Bank and a close associate of Singh in Indian policymaking, spoke recently about something former US president Barack Obama said of him in the G20 meetings: “When the prime minister speaks, the world listens.”

Singh achieved what he did because he was a special man at a special time. Ultimately, however, technocrats only succeed if those with power trust them with it. India benefited from the fact that people with power were willing to trust him to use it well at critical moments. He, in turn, provided something that today’s populists increasingly despise: knowledge, wisdom and experience. He also knew the importance of brilliant colleagues. A recent paper from the Mercatus Center describes him as “India’s finest talent scout”. In some quarters today, all this would condemn him as an embodiment of the “deep state”. That is because these people lack belief in the ideal of public service. Singh did believe in it. He believed, too, in a thriving democracy. Indeed, he thought India could not survive without one.

The economically dynamic India of today is his legacy. So, too, is his example of service to the cause of a prosperous India in harmony with the world.

martin.wolf@ft.com

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on X

Read the full article here