Eisai has warned that mandatory data collection by US health authorities could restrict patient access to the Japanese drugmaker’s new Alzheimer’s treatment.

The company said a decision by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to restrict financial support for Leqembi to Alzheimer’s patients whose doctors participate in a health agency database could have “unintended consequences”.

CMS said the database, also known as a registry, would collect evidence about how the drug works in practice and make it available to researchers to conduct studies about Leqembi and similar drugs.

It marks the first time that Medicare — the US government health scheme for people aged over 65 — has made such a data-gathering requirement mandatory for a drug deemed safe and effective by regulators.

Eisai said it is concerned the registry could hinder coverage to some groups of people who did not want to participate and raised questions about fairness. The company said it would wait to see details of the registry before it finalises spending plans to support rollout of the drug.

“There is a distinction between collecting real world evidence to understand more [about the drug] versus mandating reimbursement based on participation in that real world data collection,” Ivan Cheung, Eisai’s US chief executive, said in an interview.

“There are people who just don’t want to participate for whatever reason. It’s a free country, right?”

Leqembi, which was jointly developed by Eisai and US biotech Biogen, is poised to become the first Alzheimer’s drug that can slow progression of the disease to win traditional approval by the US Food and Drug Administration.

This month, a panel of external experts to the FDA recommended the drug be approved, a decision that would typically prompt Medicare to cover the treatment for all patients older than 65. Reimbursement by the government health scheme is critical to boosting patient access to Leqembi, which costs $26,500 per year and targets a disease that mainly affects seniors.

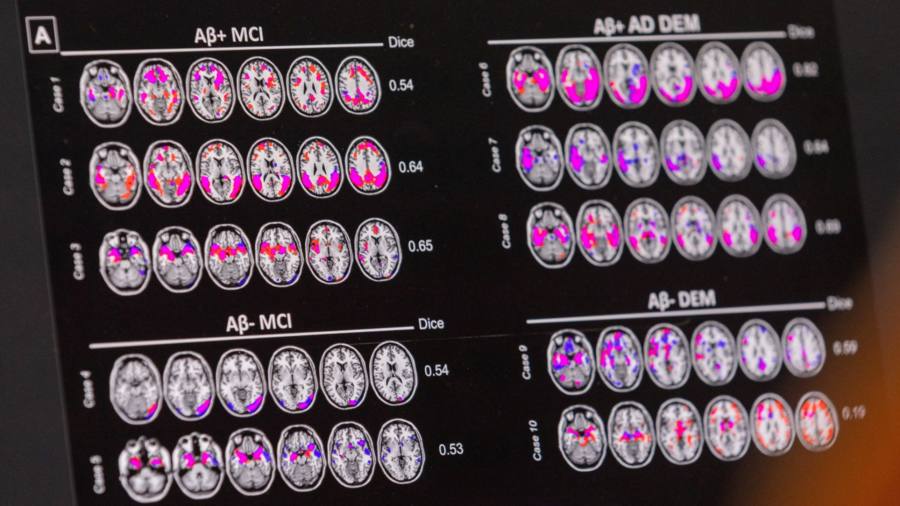

But CMS has taken a cautious approach to the new generation of Alzheimer’s drugs, which slow progression of the disease by reducing the build-up of sticky amyloid plaques in the brain.

Last year the agency imposed even tighter restrictions on Biogen’s Aduhelm and other amyloid-reducing drugs that were given the green light under a fast-track process called accelerated approval.

That decision limited reimbursement to patients enrolled in a clinical trial of the drug and caused Biogen to scrap its rollout of Aduhelm. At the time CMS cited the drug’s “potential for harm”, ranging from headaches to brain bleeding, as well as concerns about how effective it was for patients.

Eisai, which received accelerated approval for Leqembi in January, said it did not have many patients on the drug at the moment because of this requirement linking reimbursement to participation in a clinical trial.

Some researchers have warned the drugs will put a big financial burden on Medicare, with a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine estimating that Leqembi could cost the scheme more than $5bn per year. They question whether Leqembi’s efficacy — it slowed the rate of cognitive decline in early-stage Alzheimer’s patients by 27 per cent compared with placebo in a late stage trial — justifies the high price and risk of side effects.

But patient advocacy groups have strongly criticised CMS’s decisions to limit reimbursement for drugs given the green light by the FDA under both its accelerated approval process and the traditional process.

John Dwyer, president of the Global Alzheimer’s Platform Foundation, said requiring participation in a registry to access an approved drug is “unprecedented and unacceptable” for physicians and patients.

He said the CMS decision may limit access for some Alzheimer’s sufferers in rural areas or those who do not have a healthcare provider equipped to provide electronic data entry.

Rival drugmaker Eli Lilly, which is developing a similar Alzheimer’s drug, has also criticised CMS for linking reimbursement to a registry.

Wall Street analysts have said the registry requirement could delay uptake of Leqembi in the short term, as it would require physicians to sign up for a “CMS-facilitated portal”, but that it was not a big challenge over the longer term.

“We see the ongoing registry requirement (coupled with previously anticipated infrastructure build/prescriber education) as likely slowing initial uptake for the category. Our longer-term expectations for the market remain unchanged,” said JPMorgan, which forecasts the new class of anti-amyloid drugs could generate $25bn in peak sales.

CMS said in a statement it is committed to helping people obtain timely access to innovative treatments that meaningfully improve care and outcomes for Alzheimer’s disease.

Read the full article here