Roger Squires chanced upon crosswords by magic. During his first career flying for the aviation arm of the Royal Navy, periods of idleness were filled with card games played for money. But because Squires was also a self-taught magician and a member of Britain’s Magic Circle, his companions wouldn’t let him play.

For want of something to do, the lieutenant took up cryptic crosswords, setting in train a new calling that would establish him as the world’s most prolific compiler. Squires, who has died aged 91, set about 80,000 puzzles, wrote 2.5mn clues and was published in scores of publications around the world. The puzzle community called him the “Mozart of setters”, as much for his light, witty style as for his productivity.

Squires tried his hand at other professions. As well as flying and magic, he was a Butlin’s holiday camp entertainment officer and an actor, appearing in small parts in TV series such as Doctor Who and Crossroads.

But crossword setting paid the bills. Few can afford to do this full time. Yet Squires’ exceptional output — at one time a rate of nearly 40 puzzles a week — meant his cryptic crosswords would sometimes appear in five different UK national newspapers on the same day.

For the Financial Times, he was Dante — the stage name used by an American magician in the 1930s and 1940s. Guardian solvers knew him as Rufus (his initials were RFS). Squires set for The Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Independent — for everyone.

In 2015, the Guinness World Records totted up 77,854 crosswords to his name when they anointed him — not for the first time — for most crosswords compiled in a lifetime. Squires also holds the record for the longest word in a cryptic crossword — the 58-letter entry for the Welsh town Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, published in 1979 in the Telford Wrekin News. (Clue: Giggling troll follows Clancy, Larry, Billy and Peggy who howl, wrongly disturbing a place in Wales.)

Born in Wolverhampton in 1932, Squires learnt from his parents a love of poetry and prose. He attended Wolverhampton Grammar School, but his wanderlust took him to the navy aged 15. He became a lieutenant in the Fleet Air Arm, travelling around the world, occasionally writing, directing and performing in shows.

Squires’ life-changing moment came in 1961 near Sri Lanka, when his Gannet aircraft stalled and crashed into the sea. “I took a last breath from the small pocket left above me and dived out,” he recalled years later. Having been “a bit of a worrier”, the accident, which claimed the life of the pilot, caused Roger to treat life “far more light-heartedly”.

This carefree outlook underpinned his crosswords, which were often humorous: Two girls, one on each knee (7)* was his two-millionth clue. He made the cryptic double definition his métier. For example, one in a 2001 Dante puzzle is 13 down: Gave up and left (9).*

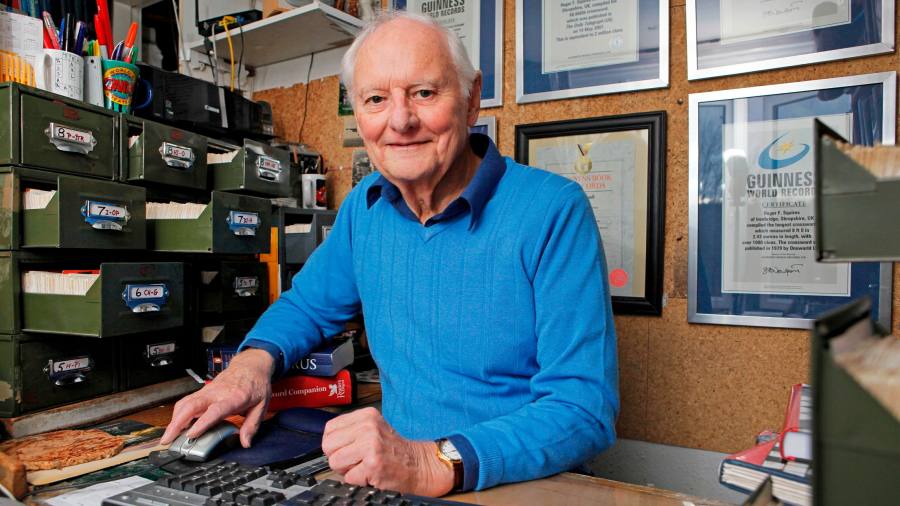

In his office looking out on the Ironbridge gorge in Shropshire, Squires wrote clues against the backdrop of television and classical music, operating an elaborate dots-and-dashes coding system that gave him recall for every clue he wrote. Scrabble tiles were used to work out anagrams. The office, adjoining his cottage, was awash with dictionaries and reference books old and new.

When challenged by editors about clues, Squires was ready to stand his ground. But having been a crossword editor himself — for the Birmingham Post over more than two decades — he understood when not to overplay his hand.

But Squires fought change when it mattered most. In 1998, The Telegraph planned to automate crossword production, cutting the crossword team and replacing them with recycled puzzles. Squires led a public revolt of compilers, dubbed the “Telegraph Six”. Boris Johnson, then an assistant editor at the paper, rang him for his views, “which I gave somewhat forcibly”, Squires recalled. Johnson called back “to eat humble pie”, reinstated the compilers and increased their fees. Waspishly, Squires clued in celebration: Submit to pressure and return to base (9)*.

An accomplished sportsman, the compiler played squash into his mid-sixties and swam regularly. He is survived by his wife, Anna, his son and two stepchildren.

When Squires announced his retirement in 2017, FT readers mourned. One from Washington wrote in to say: “Nothing in this nutty world gives me more pleasure” than Dante’s puzzles.

*Solutions — PATELLA, ABANDONED, CLIMBDOWN

Read the full article here