There are signs that the age of petroleum has passed its zenith. Adjusted for inflation, a barrel of crude oil now sells for three times the long run average. The large western oil companies, which cartelized the industry for much of the 20th century, are now selling more oil than they find, and are thus in the throes of liquidation. -James Buchan

When coal came into the picture, it took about 50 or 60 years to displace timber. Then, crude oil was found, and it took 60, 70 years, and then natural gas. So, it takes 100 years or more for some new breakthrough in energy to become the dominant source. Most people have difficulty coming to grips with the sheer enormity of energy consumption. – Rex Tillerson, former CEO of Exxon Mobil

From the moment you wake up in the morning until you go to sleep at night, your entire day revolves around energy. Consider the plastic in your alarm clock, the electricity that powers your coffee pot, the gasoline in your car that transports you to work, and the food you purchase at the grocery store. Even the heating and cooling of your home involves energy. None of these everyday activities would be possible without the consumption of fossil fuels.

We live in a technology-driven world. That technology requires energy, and that energy is provided by fossil fuels. When we think of oil, our thoughts often turn to the gasoline powering our cars or the diesel fueling our trucks. Yet, it extends far beyond that – to the internet, our smartphones, tablets and computers, space satellites, skyscrapers, factories producing goods, and the modern agriculture that sustains global food supply. It includes planes, trains, and automobiles – all of which rely on oil. Without oil and natural gas, the familiar world around us would come to a standstill.

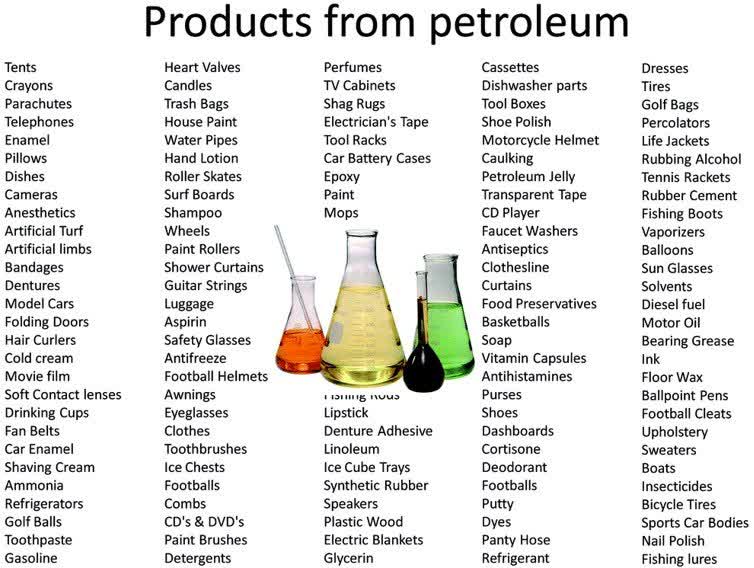

As illustrated in the table below, the reach of oil extends beyond just powering transportation. It forms the foundation for a myriad of products ranging from plastics to pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, deodorants, aspirin, paints, and roofing materials, all having a petroleum base. With thousands of products derived from oil and natural gas, its influence is pervasive. When we contemplate energy, our minds often go to the gasoline powering our cars or the jet fuels enabling global travel within hours. However, oil’s role surpasses being merely a transportation fuel. Most of the items we use daily in our homes also have a petroleum base.

Royal Society of Chemistry

Before the discovery of oil, the global population was approximately 1.7 billion. Today, it is 8 billion. The past century was defined by the age of oil, while this century is likely to be marked by oil scarcity. It’s probable that we’ll witness the peak of global oil production within the next 5-10 years. Once that occurs, economies worldwide may struggle to grow, as economic expansion is closely tied to energy production. Among all the fossil fuels we consume, oil is the most crucial due to its ubiquity in nearly every consumer product that’s manufactured, transported, or sold. Oil is deeply embedded in our contemporary economic life. Our economy runs on oil and there is nothing out there to replace it on the horizon.

I began to study peak oil in the early years of this new century. I was fortunate to befriend the late Matt Simmons of Simmons International who was kind enough to share his research with me that eventually led to the publication of his book Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy. Matt’s book highlighted the coming peak of Saudi oil production and questioned OPEC oil reserves that miraculously grew by over several hundred billion barrels between 1988-1989 without any known new discoveries. In the case of Saudi oil reserves, they jumped by 100 billion barrels and have been held constant since that time despite annual production of over 3 billion barrels a year.

Matt passed away in 2010 just as horizontal drilling, fracking, and shale oil would more than double US oil production. Peak oil was a hot topic in the ‘00 decade and Matt was a leading proponent despite the shale revolution which did nothing more than postpone its arrival. Until the advent of horizontal drilling, fracking and shale oil, conventional US oil production peaked in 1971 at roughly 10 million barrels per day (mbd). Oil production fell gradually each year, with a brief spike in the 1980s as a result of Alaskan oil. According to the International Energy Agency, production of conventional non-OPEC oil production peaked in 2007 at 46.2 mbd and now is at 44.2 mbd, 4% below its peak. If we include OPEC, conventional global output peaked in 2016 at 84.5 mbd and now has declined to 81.3 mbd. Global supply growth increased by 8.6 mbd between 2006-2015 and by 7.3 mbd between 2015-2023.

Today, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that oil consumption will increase by 2 million barrels per day to 101.9 million barrels per day, primarily driven by China and non-OECD countries. If conventional oil peaked in 2016 for OECD and OPEC countries, how did oil production increase from 84.6 million barrels per day in 2006 to this year’s forecast of 101.9 million barrels per day? Between 2006 and 2015, the growth in oil production mainly originated from US shale, Canadian oil sands, and biofuels. From 2015 to the present day, oil production grew by 7.3 million barrels per day, a significant portion of which came from the Permian Basin, with an additional 2 million barrels per day from Canadian oil sands and biofuels. This growth can be attributed to non-conventional oil sources like shale, tar sands, biofuels, gas to liquids, and coal to liquids.

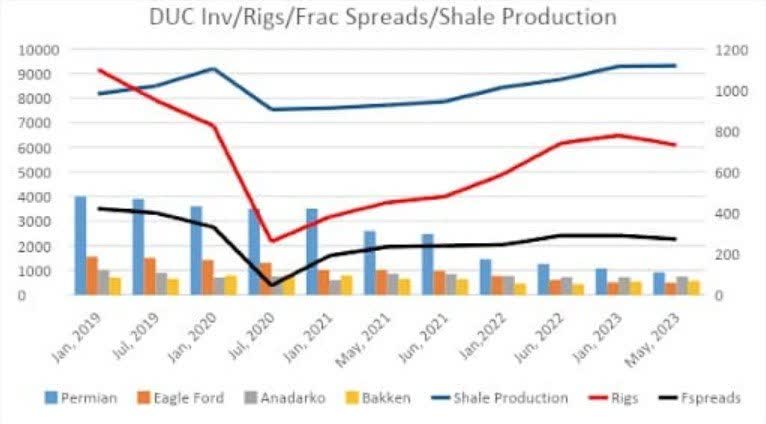

The US shale revolution has contributed to 90% of the global oil production growth over the last decade. However, it seems that US shale production is reaching its peak, which could eliminate a major source of growing oil supply. Both the Bakken and Eagle Ford shale fields have peaked, leaving primarily the Permian and Marcellus fields to increase production. Depletion rates in the Permian, which is the last significant shale play, have risen from 5.8% last year to 6.4% this year, and continue to increase. It’s estimated that the Permian could peak in the next two years. If this proves to be true, there will be no significant source of growing oil supply remaining, other than the tar sands in Canada and Venezuela and a few OPEC countries like Iran and Iraq.

According to the BP Statistical Review, of the 55 oil-producing countries and regions in the world, 46 of those countries are five years beyond their peak, leaving only 9 countries, including the US, to cover the decline in the other 46 countries in addition to meet future oil demand growth. We should have been thinking about this decades ago as energy transitions take decades and up to 50-60 years to complete.

Many people have sounded the alarm about the impending peak in oil production, yet these voices often echo as the ‘Cassandras’ of our time, dismissed, ridiculed, or overlooked by mainstream media and politicians. Rather than considering this issue, media and political discussions largely revolve around climate change, which, to some, has morphed into a quasi-religion more than a scientific discourse. I’ll delve deeper into this subject later. It’s noteworthy that the IPCC climate report makes no reference to peak oil, peak coal, or peak natural gas. These looming issues present significant threats to our economy and lifestyle, with oil posing the most immediate challenge.

Skeptics of peak oil may question its validity, considering that after a 50% decline over the past 40 years, US oil production unexpectedly bounced back, growing by 10 million barrels per day (mbd) – an amount equivalent to a new Saudi Arabia’s output – thereby reclaiming its position as the world’s leading oil producer. The shale revolution in the US significantly altered the oil dynamics of the past decade, leading Saudi Arabia to initiate an oil price war in 2014. This war caused oil prices to plummet from over $100 per barrel to under $60 per barrel, in hopes of pushing US oil producers out of business. Instead, these producers innovated, reduced production costs, and pumped even more oil, which solidified the US’s position as the world’s top oil producer.

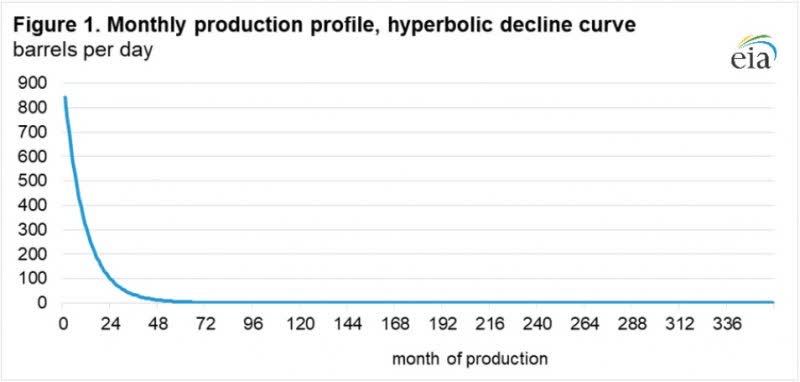

That prominence may be coming to an end. Unlike conventional oil, shale oil fields peak within the first few years of production and then fall rapidly. To maintain production, shale producers must constantly drill in order to keep production up as depletion rates accelerate after the first year of production.

Source: EIA

The swift growth of US shale production over the past decade resulted from shale producers exploiting their Tier 1 inventory, which consists of their most productive, top-quality wells. Nowadays, these shale producers are turning to their Tier 2 wells, which are less productive. Despite this, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicts that US shale production will continue to rise until the end of 2024. The primary drivers of US shale production have been the drawdowns of DUC (Drilled but Uncompleted) wells and an increased rig count, both of which are currently on the decline.

Source: OilPrice.com, US Shale Production Is Set for a Rapid Decline

Furthermore, news stories featuring predictions from industry CEOs, executives, and various media outlets have begun to forecast future declines in oil production.

Saudi Arabia said global oil production could drop 30% by the end of the decade due to falling investment in fossil fuels. —Bloomberg, 12/13/21

“The world is going back to a world that we had in the 70s and 80s.” —Ryan Lance CEO of Conoco Philips at CERAWEEK WSJ, 3/8/23

“I think the people that are in charge now [of oil] are three countries—and they’ll be in charge for the next 25 years… Saudi first, UAE second, Kuwait third.” —Scott Sheffield, CEO Pioneer Resources, 6/11/23

“The Kingdom will do its part in this regard as it announced an increase in its production capacity to 13 million barrels per day, after which the Kingdom will not have any additional capacity to increase production.” —Mohammed Bin Salman, 7/16/22

Russia’s Energy Ministry announced it was “most likely” that Russia oil production would never again hit the levels of output seen in 2019. —April 2021, The Crash Course by Chris Martenson, p.145

After inhabiting a palatial executive suite known as the “God Pod” for more than 25 years, Exxon Mobil’s top brass is downsizing to less celestial chambers. —WSJ, 5/14/23

Thus, in recent years, the three largest oil producers, known as the ‘BIG Three’ – the US, Russia, and Saudi Arabia – have all declared a forthcoming constraint on their capacity to produce more oil. Despite these announcements, both the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Energy Information Administration (EIA) continue to project that oil production growth will be there to meet future demand.

I recall a particular day when I read several articles that struck me as signs that we are edging closer to peak oil. One highlighted Amazon’s (AMZN) efforts to revamp its logistics network to expedite delivery times and curb delivery costs, primarily fuel-related. Another focused on Exxon Mobil’s (XOM) decision to abandon its extravagant “God Pod”, an executive campus designed to showcase Exxon’s global reach with features such as Anigre wood paneling and staircases from Africa, a lobby floor made of French limestone, and granite columns from Madagascar. These moves are part of an extensive effort to slash billions of dollars in costs. The former offices, lavishly furnished and sprawling over 20,000 square feet, will be replaced by a headquarters that is much more modest in both size and decor.

While many of the aforementioned headlines might be viewed as anecdotal, they convey a compelling message to those willing to listen. The three largest oil producers have expressed that oil production has hit its limit. The world’s largest public non-governmental oil company is downsizing its headquarters, and Amazon is streamlining its fulfillment centers to cut costs, mainly related to fuel, and enhance delivery times. Furthermore, a CEO of a major shale producer has stated we’re reverting to a world akin to the 1970s.

There are reasons why governmental organizations refrain from discussing ‘Peak Oil’ or predicting a decline in fossil fuel production; primarily, such discussions could undoubtedly incite widespread panic. Just consider the shortages and hoarding of toilet paper during the pandemic as a relevant example of how such news could trigger a public response.

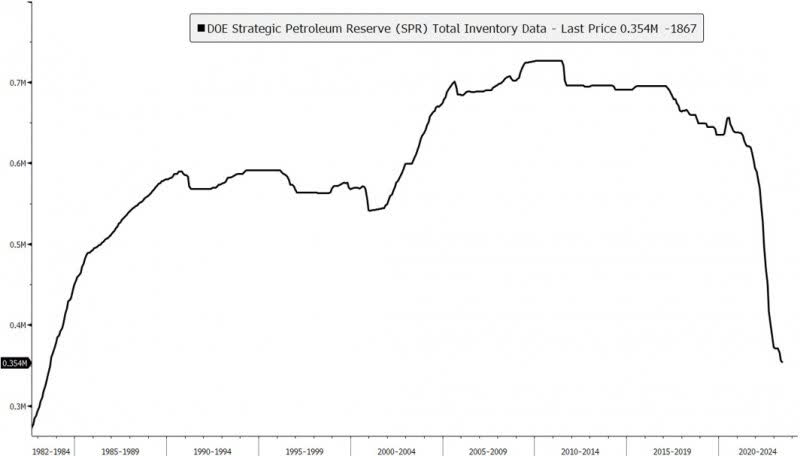

Why, then, have oil prices remained relatively low over the past year, even after peaking following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? This is partly due to the policies implemented by various governments, which have resulted in the release of hundreds of millions of barrels from their strategic oil reserves. This is illustrated in the graph below, which shows the massive drop in US Strategic Petroleum Reserves (SPR).

Source: Bloomberg, Financial Sense Wealth Management

More recently, oil traders have made a significant wager that the impending US and global recession would dampen oil demand. As a result, traders have decreased their crude oil holdings by 238 million barrels. These oil traders aren’t buying into the narrative of an oil deficit; instead, they’re concentrating solely on economic index readings, overlooking the fact that Chinese demand hit record highs in April of this year.

Traders are basing their actions on historical patterns seen during recessions, where demand typically declines marginally. They’re overlooking OPEC+’s measures intended to limit supply and rebalance the market. They’re also neglecting the falling productivity in the Permian region and the statements from shale oil CEOs about diminishing shale production. Executives from both ConocoPhillips and Pioneer Resources are predicting higher oil prices in the second half of the year, citing declining well productivity and rising costs.

Moreover, these traders are accepting the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) upgrade in expected US crude oil production growth, with a forecasted increase of 720,000 barrels per day this year. However, shale executives don’t share this optimism. In early March, shale executives stated that OPEC has once again become the most influential force in global oil supply, essentially returning leadership of the oil markets to OPEC’s hands.

Over the past decade, as we’ve begun transitioning towards a greener economy, it was suggested that electrifying our transportation fleet would reduce our dependence on oil and bring us closer to ‘Peak Demand’. Contrary to this, except for the recessionary years of 1974, 1981, 2008, and the lockdown year of 2020, oil demand has consistently risen every year since 1972. Oil consumption has increased by nearly 10 million barrels per day each decade: from 50-60 million barrels per day in the 70s, to 60-65 million barrels per day in the 80s, 70-80 million barrels per day in the 90s and 2000s, to today’s demand of 101.9 million barrels per day. Economic growth necessitates an increase in energy, and since oil remains the primary energy source, particularly for transportation fuel, economic growth invariably demands an increase in fossil fuel consumption. Today, oil accounts for over 83% of the world’s energy usage.

Traders are overlooking another critical factor: depletion. Oil wells don’t cease depleting based on economic activity. Depletion is governed by geology, not economics, and it is particularly relentless in shale basins. The production of oil wells follows a bell-shaped curve, increasing when a well is first drilled and put into production until about half of the reserves are extracted, after which production begins to decline. This decline occurs more rapidly with shale oil compared to conventional oil wells. Since oil is a geological resource, production decreases over time as more oil or minerals are drilled or mined.

We will soon find out who is correct as we move into the second half of the year: the traders or the CEOs of oil companies. If traders’ fears of a recession materialize, oil prices could soften and fall. Conversely, if the predictions of oil executives and analysts are accurate, prices could rebound dramatically. Only time will reveal the truth, but we won’t have to wait much longer to discover it. Personally, my money is on the oilmen who are actually involved in the production.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here