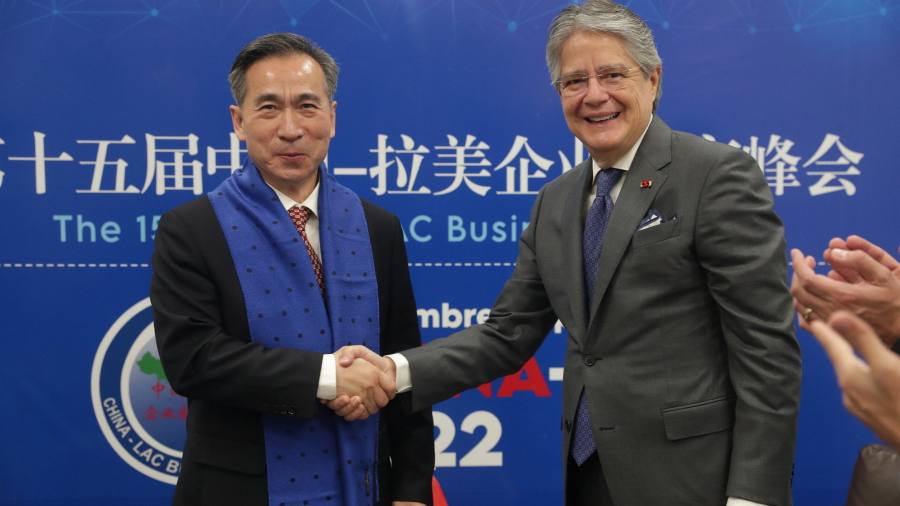

Ecuador’s president Guillermo Lasso is a US-educated, pro-business conservative. But his government has just signed a trade deal with China, and when he secured $1.4bn of debt relief last year, it was from Xi Jinping.

“Xi was very understanding,” said Lasso of the Chinese president.

Experts say Ecuador’s experience with China shows how the US and other western countries risk losing further ground in Latin America to Beijing unless they can offer better trade and investment opportunities.

Chinese trade with Latin America has exploded this century from $12bn in 2000 to $495bn in 2022, making China South America’s biggest trading partner.

Chile, Costa Rica and Peru have free trade deals with Beijing, Ecuador inked its agreement this month and Panama and Uruguay are planning treaties.

The Biden administration, however, has ruled out new trade agreements, frustrating Latin American nations. The EU has spent 20 years negotiating a free trade deal with the South American Mercosur bloc but has yet to ratify it.

Eric Farnsworth, who heads the Washington office of the Council of the Americas, a regional business group, said there was growing bipartisan concern about the lack of an active US trade agenda for Latin America.

“You have to compete economically in the western hemisphere or you’ll lose it,” he said. “And we’re not competing effectively.”

The US has a patchwork of six existing free trade agreements covering 12 Latin American countries, but the lack of a common framework has led to struggles to integrate regional value chains.

Ricardo Zúniga, principal deputy assistant secretary in the US state department’s western hemisphere bureau, conceded that “our political reality right now is that there’s not support for expansion of free trade agreements”. The US was focusing on “taking advantage of trade facilitation and . . . nearshoring opportunities”.

Trade is not the only issue. Beijing has won friends in Latin America by building and financing roads, bridges and airports. More than 20 Latin American and Caribbean nations have joined China’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative and China has lent more than $136bn to Latin American governments and state companies since 2005.

The US and EU, meanwhile, have been focusing on corruption, democracy, the environment, human rights and the risks of doing business with China. The EU’s Global Gateway initiative, envisioned as a response to the BRI, has pledged just $3.5bn to Latin America.

Among the US’s talking points with Latin America is an entreaty to avoid 5G phone networks built by China’s Huawei, which is sanctioned by Washington — but US and European alternatives to Huawei are often more expensive.

A Latin American foreign minister last year compared the American approach to the Catholic religion, telling the Financial Times that “you have to go to confession and you still may end up being damned”.

The Chinese, by contrast, were like the Mormons who “knock on your door, ask how you are feeling” and “want to help”.

Zúniga rejected the criticism that the Biden administration had put too much emphasis on human rights. “The erosion of human rights and economic performance go together,” he said. “When you have leaders that concentrate powers in their own hands, inevitably they start making economic decisions that are not actually consistent with the national interest.”

Yet the contrast between visits made this year by Brazil’s newly elected president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to the world’s two top powers was telling.

Lula visited Washington with a small delegation for one day in February and met president Joe Biden. A White House statement afterwards said that talks had focused on democracy, human rights and climate change. Trade and investment were mentioned, but no deals were announced.

In April, the Brazilian leader spent three days in China, bringing dozens of business leaders and state governors. About 20 agreements worth $10bn were signed. Lula made a point of touring Huawei’s research centre in Shanghai, saying afterwards that “no one will prohibit Brazil from improving its relationship with China”.

Brazil also signed agreements to pursue semiconductor technology, renewable energy and satellite surveillance. The deals form part of its strategy of “active non-alignment”, which resists taking sides between the west and China or Russia, including over the war in Ukraine.

While China has been steadily investing and building trade, the US has launched initiative after initiative, to little avail. The Trump administration unveiled América Crece (Growth in the Americas) in 2019 to try to counter Beijing’s BRI push, but it delivered few results.

The Biden administration then tried Build Back Better World, a proposed infrastructure alliance announced in June 2021. But Panama’s president Laurentino Cortizo told the FT last month that nothing had come of it. “The speeches are very pretty,” he said, adding that the US should “firm up the promises . . . of economic support”.

Last June Biden announced yet another US initiative, the “Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity”. But almost a year later, specific investments have yet to be announced and Brazil and Argentina, two of the region’s top three economies, have not joined. “Latin Americans still aren’t quite sure what it will entail,” said Margaret Myers of the Inter-American Dialogue think-tank in Washington.

One obstacle is funding. The DFC, the main US development finance institution, is required to prioritise low and lower-middle income countries, which rules out most of Latin America. Multilateral development banks also have restrictions on lending to upper-middle income and high-income nations. China has no such issue.

European leaders are meanwhile trying to remedy nearly a decade of neglect by convening a summit with Latin American presidents in July. But one EU diplomat admits: “If we fail, there may not be another summit. It’s a last chance to relaunch the relationship.”

At the same time, European and US companies have been selling assets in the region, put off by its fraught politics and keen to refocus on “core” geographies. The Chinese are ready buyers.

“It’s all very well to talk about investment but US and European companies are shedding their assets in Latin America,” said Myers. “We have to create incentives for them to stay.”

The disinvestment trend includes strategic areas such as renewable energy and critical minerals. Duke Energy of the US sold 10 hydroelectric dams in Brazil to China’s Three Gorges Power in 2016 as it refocused on its home market. Canada’s Nutrien sold its 24 per cent stake in Chile’s SQM, one of the world’s biggest lithium producers, to a Chinese company in 2018.

Italy’s Enel sparked concern that it was handing a near-monopoly over Peru’s electricity to the Chinese after announcing last month that it would sell its assets for $2.9bn to China Southern Power Grid. Spain’s Naturgy sold its Chilean power distribution to the Chinese in 2020.

Brazil’s finance minister Fernando Haddad complained while in Beijing: “We’re almost going through a period of US disinvestment with companies leaving the country.” Ford is among them; it is discussing selling one of its former factories there to China’s BYD to build electric vehicles.

“We are giving lots of directions, mandates and conditionality,” Farnsworth at the Council of the Americas concluded of the US strategy in the region. “What’s missing is market access and investment. The Chinese say: ‘We don’t care how you run your country. Just let us take your lithium.’”

Read the full article here