Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

One of the most significant intellectual influences on key figures in the Trump administration is Curtis Yarvin, an American computer engineer-turned-blogger who believes that the game is up for US democracy and only a latter-day monarch or national “CEO” can save America.

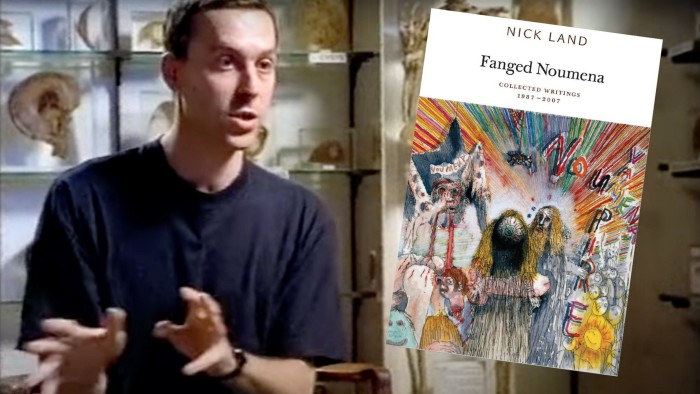

A second name that crops up in connection to Trumpworld’s philosophy is that of Nick Land, an Englishman and former academic. Together, the pair have come to be recognised as the twin eminences of a predominantly online movement known as neoreaction or the Dark Enlightenment.

Seeing references to Land transports me back to the early 1990s, when I spent a year studying for a master’s degree in philosophy at the University of Warwick. He was then a charismatic young lecturer, not yet the dark magus of anti-democratic neoreaction that he is today.

In those days, Land described himself as a “delirial engineer” — a follower of marginal thinkers such as the French writer Georges Bataille, who sought to liberate the forces of unconscious desire that the rationalism of the Enlightenment was meant to hold in check.

His work was also a celebration of capitalism, or rather of the fearsome power of the market to dissolve settled ways of life. Accelerating capitalism could usher in a new set of social relations, he believed, or hasten the “singularity” in which the biological and technological merge.

As the Nineties wore on his behaviour became increasingly erratic. He started living in his office on campus. He eventually left his academic post in 1998 and moved to China. I didn’t hear of him again until 2011, when a small independent publisher put out a collection of his essays called Fanged Noumena.

The years spent overseas had left their mark. What once looked like a tactical embrace of the market had turned into veneration of a “globally ascendant Sino-capitalism”. In a breathless paean to the “turbo-charged Shanghai economy” he rhapsodised about a “perfect complicity between radical innovation and profound conservatism”.

Over the next few years his theories gained traction among the US-based far-right. During the first Trump administration, as journalists started to cite Land in their attempts to understand the “alt-right”, I tracked him down. In an email exchange he told me that China and east Asian statelets like Hong Kong or Singapore came closest to what he regarded as a model of “competent government”. He has also praised their lack of “social terror”, which he attributes to ethnically homogenous populations.

Land, like Yarvin, believes the ideal state should function like a business. According to this theory, which Yarvin calls “neocameralism”, a properly constituted state is one that has been cured of democracy. Its guiding principle is “no voice, free exit”: the residents or clients (not citizens) of such a state have no rights, but do have the ability to take their custom elsewhere.

One of the touchstones for Land and others on what is sometimes called the “techno-commercial” wing of neoreaction is an article written in 2009 by the Silicon Valley billionaire and now prominent Donald Trump supporter Peter Thiel (who also happens to have been an investor in Yarvin’s start-up, Urbit). “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible,” Thiel wrote. The fate of the world “may depend on the effort of a single person” able to make the world “safe for capitalism”.

Land’s Thiel-inspired vision for a “hard reboot” of the western world, set out in a long essay entitled “The Dark Enlightenment”, includes the dismantling of democracy and a massive downsizing of government. Once an obscure idea, it sounds a lot like what Trump confidant Steve Bannon used to call the “deconstruction of the administrative state”. That, Land told me, “is definitely [something] my type of neoreactionaries would endorse. To the point of euphoria.”

I contacted him again recently, and asked if he’d respond in the same way to what Elon Musk and the so-called Department of Government Efficiency are doing by gutting federal agencies. “The answer,” Land said, “is definitely yes.”

Read the full article here