“What did Mike Tyson say? You have the best plans and then you get hit in the face,” quips Antony Blinken when I ask him to take stock of the past four years.

“We faced the worst economic crisis arguably since the Great Depression. We faced the worst public health crisis in at least 100 years. We had strong divisions at home, a challenge to our democracy, and we had very fraught relations with our closest allies and partners.”

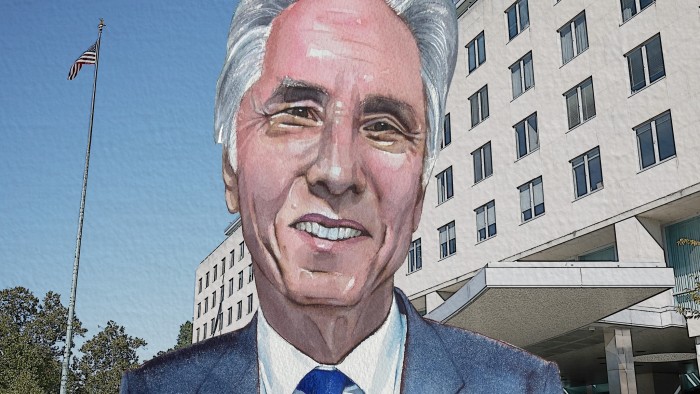

Today the US is grappling with many foreign policy crises around the world, from Ukraine and Gaza to Syria. But the outgoing US secretary of state is anything but downbeat about the record of the Biden administration. Back in 2021, he says, adversaries believed the US was in “inexorable decline”. Since then, big investments at home, including in infrastructure and the domestic chip industry, in addition to intense work with allies, have changed the landscape. “We’re now operating from a position of strength.”

We are meeting at Central Michel Richard, an upscale bistro in Washington, where I arrive hoping America’s top diplomat will join me in some liquid holiday cheer. “I’m good with that,” Blinken says at first, indicating the water on the table. But I press the point and he relents. “I probably shouldn’t, but why not.”

Blinken orders a glass of Cabernet Sauvignon. I pick a Burgundy, prompting a flicker of anxiety in my guest. “I hope I actually got an American Cabernet,” he frets. Blinken, 62, is a Francophile who speaks fluent French from his teenage years living in Paris. But buying non-US products can be risky for officials. (His wine turns out, thankfully, to be Californian.)

Blinken has just returned from a tour of the Middle East to discuss the situation in Syria after the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime. He says the trip to Jordan, Turkey and Iraq generated some alignment between countries about expectations for the interim authorities in Damascus by creating a “road map”, but cautions that the situation is “very fraught”.

“It’s a moment of incredible possibility, especially after the horrors of the Assad dictatorship . . . but we’ve seen too many times when one dictator’s been replaced by another,” he explains. “It was very important that we get in there early and try to bring everyone together, which we did.”

Blinken was surprised at how quickly the regime fell, which he says was partly due to the pressure the US has been putting on Assad’s patrons Russia and Iran. “They were in no position to actually come to his rescue.”

As our wine arrives, I mention that Israel’s prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu claimed it was Israeli pressure on Iran that created the conditions for the collapse. Without revealing the frustration many in the Biden administration feel about Netanyahu, he replies carefully.

“I imagine the prime minister would be among the first to acknowledge that the unprecedented support we gave to Israel, faced with unprecedented attacks from Iran, was a huge difference maker,” he says. “Iran is not in much of a position to pick a fight with anyone . . . That had real repercussions for Syria in a positive way.”

The challenge, he adds, is to translate the current situation into a “positive and enduring” outcome and to provide “the best possible hand to the Trump administration so that they can take the baton”.

He thinks Trump will be motivated partly because of his success in his first term completing the elimination of Isis’s territorial caliphate. “I imagine that he has a strong incentive in not seeing Isis re-emerge.”

I am conscious that we have only 90 minutes. “Shall we order?” I suggest. “I don’t want to send you back starving.”

“I’m only doing this because it’s a free meal,” he jokes. “I so rarely get out for lunch that it’s a great opportunity to start to reintegrate.”

Blinken and his wife Evan Ryan, the White House cabinet secretary, have two small children (aged four and five) so they have little spare time. He has also spent 12 months of the past four years travelling the world. How do they manage, I ask? His wife’s parents live with them and help look after their kids, he tells me.

Do they get a salary? “They could easily ask, and I would do it,” he says with a smile.

As the waiter hovers, we talk about the restaurant scene in Washington, which has changed markedly since he was an intern at The New Republic magazine in the 1980s. “Back in the day, you could count the restaurants on one hand. Now, at least what I’m told, it’s quite a different scene.”

Central was opened by French chef Michel Richard, whose obituary in the Washington Post noted he had brought “Gallic flair” to “a city long belittled as a stodgy outpost of steakhouses and uninspired cuisine”.

Our menu is not uninspiring. Blinken chooses a kale salad and the Atlantic salmon. I pick a tarte Alsacienne — bacon, onions and crème fraîche on thin pastry — and opt for the salmon as well.

Blinken says that his “greatest satisfaction” was rebuilding alliances, pointing to Biden’s efforts to “connect the Atlantic and the Pacific” and show that “what happens in one theatre has profound consequences in the other”.

He notes that four Indo-Pacific countries — Japan, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea — were invited to attend Nato summits during the Biden administration and that the transatlantic alliance now criticises China, which was previously unimaginable. He recalls how former Japanese prime minister Fumio Kishida warned that “Ukraine [today] might be east Asia tomorrow”, in a veiled reference to China.

I ask why Nippon Steel’s $15bn acquisition of US Steel has faced such opposition in the administration as a security threat, even though Japan is the most important US ally in Asia. An inter-agency panel is reviewing the deal, but critics say the president has politicised the process.

Does Blinken concede that it is causing tensions? “We’ve worked to be very clear and transparent with our Japanese allies about what the considerations are . . . Let me just leave it at that.”

The presence of North Korean soldiers fighting with Russians against Ukraine has further underscored how conflicts in one region have implications for nations in other parts of the world. Giving another example, Blinken stresses that Chinese groups are still providing Russia with critical materiel to help it rebuild its defence industry base.

“This is . . . powerful evidence to Europeans that the biggest threat to their security . . . is unfortunately being driven in part by the contributions of countries that are halfway around the world in the Indo-Pacific.”

Blinken has repeatedly lambasted China for allowing companies to send dual-use items with both civilian and military applications to Russia. The flow of trade has not fallen, so I ask why the administration has not taken actions with more teeth.

“They’ve been trying to have it both ways,” says Blinken, a reference to China also claiming to want to help bring peace to Ukraine. He says “China is hearing a chorus of concern from many countries” who along with the US have imposed sanctions on Chinese entities aiding the Russian war effort.

I push again, saying the US sanctions don’t appear to have changed the calculus in Beijing. “It’s not flipping a light switch, but I think it’s putting China in an increasingly difficult position . . . They certainly don’t like the actions that we’ve taken against Chinese entities. And I imagine that there’ll be more to come as necessary, including in the weeks ahead.”

His worst moment as secretary of state came when 13 members of the US military died in Kabul in 2021 during the withdrawal from Afghanistan — the botched handling of which is widely seen as a big failure for Biden. Blinken defends the decision to withdraw when the US did, however, saying that its adversaries wanted Washington to remain “bogged down” in Afghanistan. But he stresses that the deaths were “incredibly hard”.

Another “painful moment” was the brutal Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 2023, and then the ensuing suffering of innocent civilians in Gaza.

Biden has been criticised for failing to put more pressure on Netanyahu to cut civilian casualties in Gaza, with some critics accusing the president of not doing enough to prevent a genocide. As he prepares to leave office, I ask if Blinken thinks the US has the appropriate balance between supporting Israel and helping Palestinians?

He says the US has three goals: to stand with Israel and prevent another October 7, to avoid a wider war, and to do everything possible to protect innocent Palestinians. He says the situation is “uniquely difficult” because Hamas is enmeshing itself in the population, but that has not “removed Israel’s responsibility for doing whatever it can, both to avoid civilian casualties and to . . . ensure that assistance gets to people.”

I am also curious how he views the situation in Gaza compared to Xinjiang, where the Chinese government has detained more than 1mn Uyghurs in a persecution campaign. In his 2021 Senate confirmation hearing, he said China was committing “genocide” against the Uyghurs. Could the same conclusion not be drawn for the tens of thousands of innocent civilians in Gaza? Blinken simply says “No”.

Our food arrives. The kale salad looks big enough to feed a small embassy. The salmon is decorated with broccolini, carrots, bamboo shoots and mushrooms, surrounded by a red pepper coulis.

Looking at the vast array of challenges in the world and China’s growing clout, does Washington still have the capacity to lead? Blinken says the US has no choice but to assert leadership, partly to avoid a vacuum being filled by a bad actor. But he says there’s a “greater premium than ever” on co-operating with other nations to create more leverage to respond to China.

Critics say those efforts, however well intentioned, have had little impact on Beijing. But Blinken pushes back, citing the lectures he gets from Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, as proof of success.

“The last time I saw him, in Laos, he accused me half-jokingly, half-seriously of being on an encirclement tour, because I was going to Laos, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore and Mongolia on that trip,” he says.

Blinken is making headway with his salad so I decide to refrain from asking why anyone would eat kale. My tarte Alsacienne, on the other hand, is lush.

As Blinken has engaged with allies, he and other US cabinet secretaries have also stepped up engagement with China in the two years since Beijing flew a spy balloon over the US. Some critics describe the efforts as “zombie diplomacy” and say engaging with China is futile, but he says the US has a “responsibility” to talk to Beijing despite big differences.

I am curious if he thinks the engagement helped reduce the odds of a conflict with China over Taiwan? “Yes,” he says emphatically. “Certainly [of an] accidental [conflict] and possibly even deliberate.”

Blinken says allies had also been worried that US relations with China were veering out of control and wanted the countries to step up efforts to reduce the turbulence. One of the big questions as Trump prepares to take office is what stance he will take on China and in what fashion he will enlist US allies and partners to help.

Noticing the lack of turbulence in my glass, the waiter asks if I would like a second. I reply in the affirmative, before looking towards Blinken who resists the temptation. “I’m still nursing this one.”

Switching to the war in Ukraine, I ask how seriously the US viewed the nuclear sabre-rattling by Russian President Vladimir Putin. Biden often referred to the risk of escalation in deciding not to provide certain weapons that Kyiv had requested.

Blinken says the US was “very concerned” because Putin seemed to be at least considering the nuclear option. “Even if the probability went from 5 to 15 per cent, when it comes to nuclear weapons, nothing is more serious.”

But nuclear weapons was also one of the few issues where China may have helped the US, despite Beijing’s support for Russia. “We have reason to believe that China engaged Russia and said: ‘Don’t go there’,” he says.

He adds that a similar dynamic may have occurred when the US told China that Putin was planning to put a nuclear weapon in space.

The waiter has cleared our plates. But Blinken tells his nearby hovering aide that he needs a few minutes on Ukraine. He stresses that Putin has suffered a “strategic defeat” and that Nato is bigger and more resourced than ever. Without mentioning Trump’s criticism that Europe must do more, he says US allies have provided $150bn in addition to the $100bn from Washington. “I don’t think anyone can complain that they haven’t done their fair share.”

He also pushes back on suggestions that the Biden administration dragged its feet in providing weapons, saying it had to take into account a range of factors such as whether Ukraine could operate and maintain the systems.

We are approaching the end of our allotted time. Blinken is a huge music lover who plays guitar and posts his own songs on Spotify. Will this be his next act? “Given the love and respect I have for the American people, I should not inflict any more music on them,” he says.

Friends and critics like to say that Tony — as he is universally known in Washington — is “too nice”. What does he make of that? He pauses before saying a good diplomat must be able to listen especially when also being assertive, but then adds what could be a veiled warning to critics.

“I suspect that it’s also true that anyone who’s had the immense privilege of being given this responsibility as secretary of state has not been nice all the time.”

Demetri Sevastopulo is the FT’s US-China correspondent

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here