Russia’s military prepared detailed target lists for a potential war with Japan and South Korea that included nuclear power stations and other civilian infrastructure, according to secret files from 2013-2014 seen by the Financial Times.

The strike plans, summarised in a leaked set of Russian military documents, cover 160 sites such as roads, bridges and factories, selected as targets to stop the “regrouping of troops in areas of operational purpose”.

Moscow’s acute concern about its eastern flank is highlighted in the documents, which were shown to the FT by western sources. Russian military planners fear the country’s eastern borders would be exposed in any war with Nato and vulnerable to attack from US assets and regional allies.

The documents are drawn from a cache of 29 secret Russian military files, largely focused on training officers for potential conflict on the country’s eastern frontier from 2008-14 and still seen as relevant to Russian strategy.

The FT has this year reported on how the documents contain previously unknown details on operating principles for the use of nuclear weapons and outline scenarios for war-gaming a Chinese invasion and for strikes deep inside Europe.

Asia has become central to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s strategy for pursuing the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and his broader stance against Nato.

In addition to its increased economic reliance on China, Moscow has recruited 12,000 troops from North Korea to fight in Ukraine while bolstering Pyongyang economically and militarily in return. After firing an experimental ballistic missile at Ukraine in November, Putin said “the regional conflict in Ukraine has taken on elements of a global nature”.

William Alberque, a former Nato arms control official now at the Stimson Center, said that, together, the leaked documents and recent North Korean deployment proved “once and for all that the European and Asian theatres of war are directly and inextricably linked”. “Asia cannot sit out conflict in Europe, nor can Europe sit idly by if war breaks out in Asia,” he said.

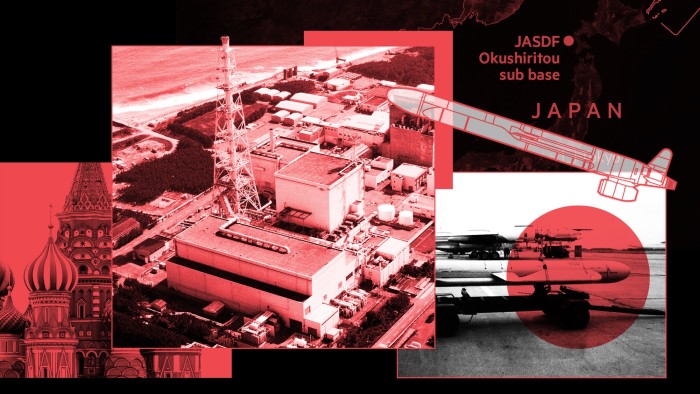

The target list for Japan and South Korea was contained in a presentation intended to explain the capabilities of the Kh-101 non-nuclear cruise missile. Experts who reviewed it for the FT said the contents suggested it was circulated in 2013 or 2014. The document is marked with the insignia of the Combined Arms Academy, a training college for senior officers.

The US has significant forces gathered in South Korea and Japan. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, both countries have joined the Washington-led export control coalition to put pressure on the Kremlin’s war machine.

Alberque said the documents showed how Russia perceived the threat from the west’s allies in Asia, who the Kremlin fears would pin down or enable a US-led attack on its military forces in the region, including missile brigades. “In a situation where Russia was going to attack Estonia out of the blue, they would have to strike US forces and enablers in Japan and Korea as well,” he said.

Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s spokesman, did not respond to a request for comment.

The first 82 sites on Russia’s target list are military in nature, such as the central and regional command headquarters of the Japanese and South Korean armed forces, radar installations, air bases and naval installations.

The remainder are civilian infrastructure sites including road and rail tunnels in Japan such as the Kanmon tunnel linking Honshu and Kyushu islands. Energy infrastructure is also a priority: the list includes 13 power plants, such as nuclear complexes in Tokai, as well as fuel refineries.

In South Korea, the top civilian targets are bridges, but the list also includes industrial sites such as the Pohang steelworks and chemical factories in Busan.

Much of the presentation concerns how a hypothetical strike might unfold using a Kh-101 non-nuclear barrage. The example chosen is Okushiritou, a Japanese radar base on a hilly offshore island. One slide, discussing such an attack, is illustrated with an animated gif of a large explosion.

The slides reveal the care Russia took in selecting the target list. A note against two South Korean command-and-control bunkers includes estimates of the force required to breach their defences. The lists also note other details such as the size and potential output of facilities.

Photographs of buildings at Okushiritou, taken from inside the Japanese radar base, are also included in the slides, along with precise measurements of target buildings and facilities.

Michito Tsuruoka, an associate professor at Keio University and a former researcher at Japan’s Ministry of Defence, said conflict with Russia was a particular challenge for Tokyo if it was the result of Russia spreading the conflict from Europe — so-called “horizontal escalation”.

“In a conflict with North Korea or China, Japan would get early warnings. We might have time to prepare and try to take action. But when it comes to a horizontal escalation from Europe, it will be a shorter warning time for Tokyo and Japan would have fewer options on its own to prevent conflict.”

While the Japanese military, and the air force in particular, has long been concerned about Russia, Tsuruoka said Russia “is not often seen as a security threat by ordinary Japanese”.

Russia and Japan have never signed an official peace treaty to end the second world war because of a dispute over the Kuril Islands. The Soviet army seized the Kurils at the end of the war in 1945 and expelled Japanese residents from the islands, which are now home to about 20,000 Russians.

Fumio Kishida, the then-prime minister of Japan, stated in January that his government was “fully committed” to negotiations on the issue.

Dmitry Medvedev, former president of Russia, said on X in response: “We don’t give a damn about the ‘feelings of the Japanese’ . . . These are not ‘disputed territories’ but Russia.”

Russia’s plans show a confidence in its missile systems that has since been proven to be overstated. The hypothetical mission against Okushiritou involved using 12 Kh-101s launched from a single Tu-160 heavy bomber. The document assesses the chance of destroying the target at 85 per cent.

However, Fabian Hoffmann, a doctoral research fellow at the University of Oslo, said that during the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Kh-101 proved less stealthy than anticipated and struggled to penetrate areas with layered air defences.

Hoffmann added: “The Kh-101 features an external engine, which is a common characteristic of Soviet and Russian cruise missiles. However, this design choice significantly increases the missile’s radar signature.”

Hoffmann also noted that the missile had proved less accurate than hoped. “For missile systems with limited yield that rely on pinpoint accuracy to destroy their targets, this is an obvious problem,” he said.

A second presentation on Japan and South Korea offers a rare insight into Russia’s habit of regularly probing its neighbours’ air defences.

The report summarises the mission of a pair of Tu-95 heavy bombers, sent to test the air defences of Japan and South Korea on February 24 2014. The operation coincided with Russia’s annexation of Crimea and a joint US-Korean military exercise, Foal Eagle 2014.

The Russian bombers, according to the file, left the long-range aviation command’s base at Ukrainka in the Russian Far East for a 17-hour circuit around South Korea and Japan to record the responses.

It notes that there were 18 interceptions involving 39 aircraft. The longest encounter was a 70-minute escort by a pair of Japanese F4 Phantoms which, according to the Russian pilots, were “not armed”. Only seven of the interceptions were by fighter aircraft carrying air-to-air missiles.

The route almost identically matches that taken by two Tu-142 maritime patrol aircraft earlier this year when they circumnavigated Japan during strategic exercises in the Pacific in September, including a flight over the disputed area near the Kurils.

Read the full article here